Monosaccharides (mono- = “one”; sacchar- = “sugar”) are monomers and a type of carbohydrate and are simple sugars, the most common of which is glucose. Monosaccharides have a formula of , and they typically contain three to seven carbon atoms.

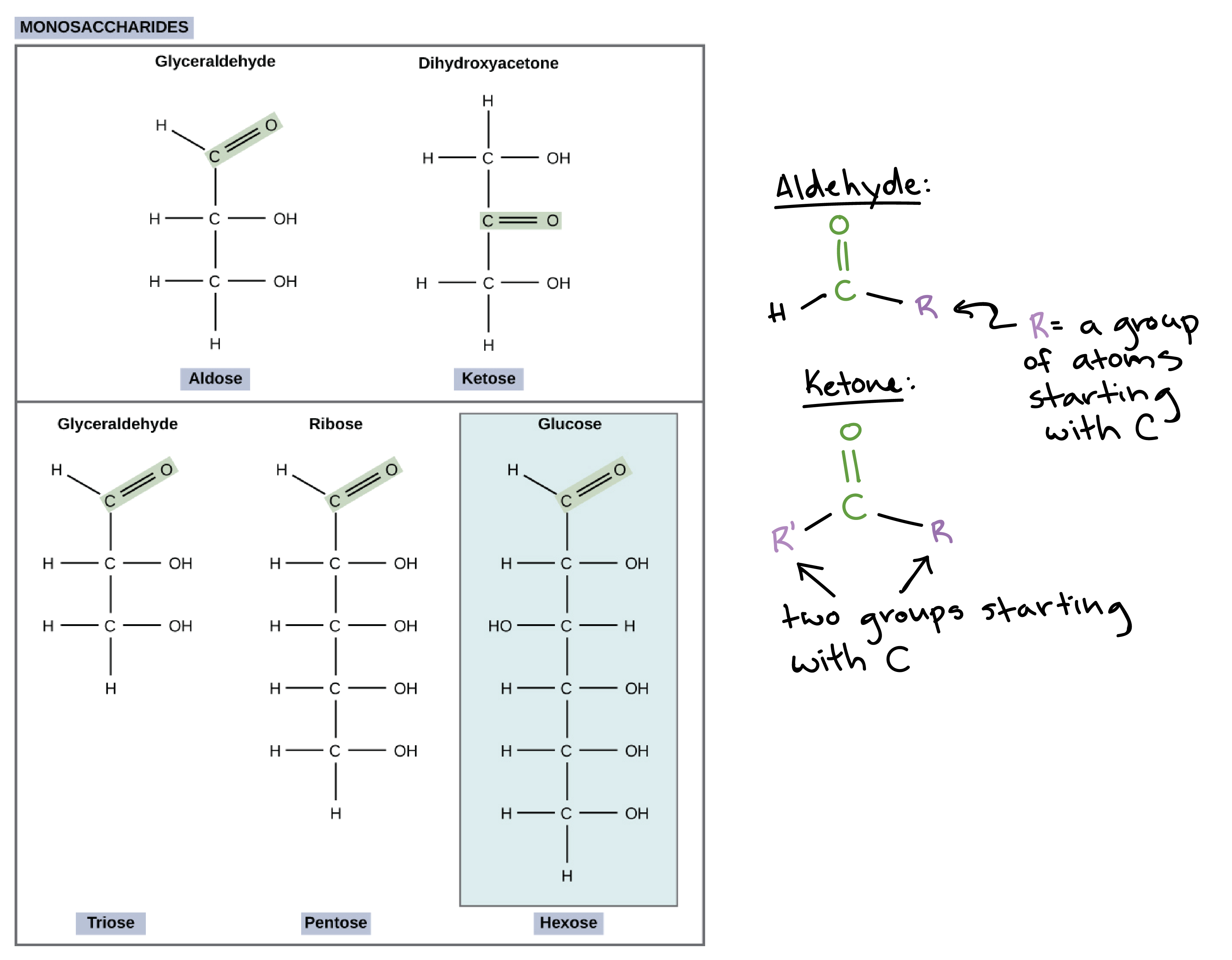

Most of the oxygen atoms in monosaccharides are found in hydroxyl () groups, but one of them is part of a carbonyl () group. The position of the carbonyl () group can be used to categorize the sugars:

- If the sugar has an aldehyde group, meaning that the carbonyl C is the last one in the chain, it is known as an aldose.

- If the carbonyl C is internal to the chain, so that there are other carbons on both sides of it, it forms a ketone group and the sugar is called a ketose.

Sugars are also named according to their number of carbons: some of the most common types are trioses (three carbons), pentoses (five carbons), and hexoses (six carbons).

Glucose and its isomers

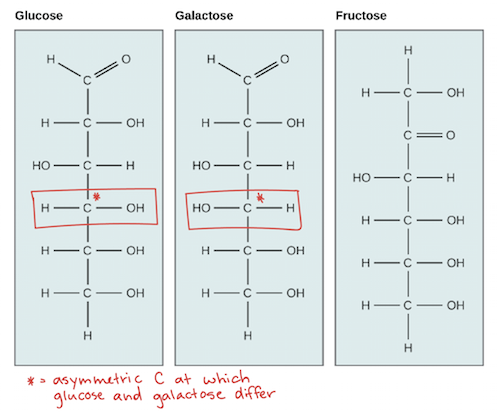

One important monosaccharide is glucose, a six-carbon sugar with the formula . Other common monosaccharides include galactose (which forms part of lactose, the sugar found in milk) and fructose (found in fruit).

Glucose, galactose, and fructose have the same chemical formula (), but they differ in the organization of their atoms, making them isomers of one another. Fructose is a structural isomer of glucose and galactose, meaning that its atoms are actually bonded together in a different order.

Glucose and galactose are stereoisomers of each other: their atoms are bonded together in the same order, but they have a different 3D organization of atoms around one of their asymmetric carbons. You can see this in the diagram as a switch in the orientation of the hydroxyl () group, marked in red. This small difference is enough for enzymes to tell glucose and galactose apart, picking just one of the sugars to take part in chemical reactions.

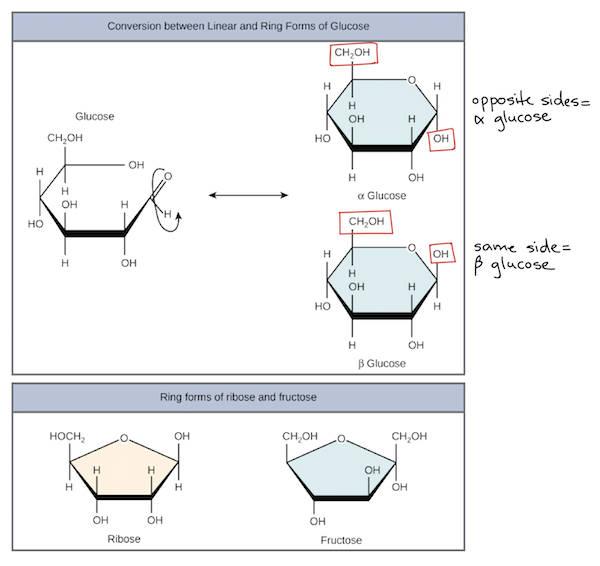

Ring Forms of Sugars

Many five- and six-carbon sugars can exist either as a linear chain or in one or more ring-shaped forms. These forms exist in equilibrium with each other, but equilibrium strongly favors the ring forms (particularly in aqueous, or water-based, solution). For instance, in solution, glucose’s main configuration is a six-membered ring. Over 99% of glucose is typically found in this form.

Even when glucose is in a six-membered ring, it can occur in two different forms with different properties. During ring formation, the from the carbonyl, which is converted to a hydroxyl group, will be trapped either “above” the ring (on the same side as the group) or “below” the ring (on the opposite side from this group). When the hydroxyl is down, glucose is said to be in its alpha (α) form, and when it’s up, glucose is said to be in its beta (β) form.