Key Points

- Innate behavior is behavior that’s genetically hardwired in an organism and can be performed in response to a cue without prior experience.

- Reflex actions, such as the knee-jerk reflex tested by doctors and the sucking reflex of human infants, are very simple innate behaviors.

- Some organisms perform innate kinesis, undirected change in movement, and taxis, directed change in movement, behaviors in response to stimuli.

- Fixed action patterns consists of a series of actions triggered by a key stimulus. The pattern will go to completion even if the stimulus is removed.

- Scientists can test if a behavior is innate by providing a stimulus to naive—untrained—animals and to see if the behavior is automatically triggered.

Introduction

Innate behavior is behavior that’s genetically hardwired in an organism. Given the right cues, an organism will perform an innate behavior without the need for prior experience or learning. Innate behaviors tend to be very predictable and they are often performed in a very similar way by all members of a species.

Reflexes

A simple example of an innate behavior is a reflex action: an involuntary and rapid response to a stimulus, or cue.

One example of a human reflex action is the knee-jerk reflex. To test this reflex, a doctor taps the tendon below your kneecap with a rubber hammer. The tap activates nearby neurons, causing your lower leg to kick involuntarily. This automatic response depends on circuits of neurons that run between the knee and the spinal cord (without involving the brain).

Some reflexes are present in human babies abut are lost or placed under conscious control as the baby grows older. For instance, a newborn baby will suck at anything that touches the roof of its mouth. This reflex helps the baby get food by ensuring it will such at its mother’s breast or a bottle placed in its mouth.

Kinesis and Taxis

Some organisms have innate behaviors in which they change their movement in response to stimulus, such as high temperature or a tasty food source.

In kinesis, an organisms changes its movement in a non-directional way—e.g., speeding up or slowing down—in response to a cue. For example, woodlice move faster in response to temperatures that are higher or lower than their preferred range. The movement is random, but the higher speed increases the chances that the woodlouse will make its way out of the bad environment.

Taxis is a form of movement behavior that involves movement towards or away from a stimulus. This movement can be in response to light, known as phototaxis; chemical signals, known as chemotaxis; or gravity, known as geotaxis—among other stimuli. It can also be directed towards, positive, or away from negative, the source of the stimulus.

For example, woodlice show negative phototaxis, meaning that they’ll move away from a light source. This behavior may be helpful because woodlice require a moist environment, and a sunny, light, spot is more likely to be war and dry.

Fixed Action Patterns

A fixed action pattern is a predictable series of actions triggered by a cue, sometimes called the key stimulus. Though a fixed action pattern is more complex than a reflex, it’s still automatic and involuntary. Once triggered, it will go on to completion, even if the key stimulus is removed in the meantime.

Egg Retrieval

A well-studied example of a fixed action pattern occurs in ground-nesting water birds, like graylag geese. If a female graylag goose’s egg rolls out of her nest, she will instinctively use her bill to push the egg back into the nest in a series of very stereotyped, predictable movements. The sight of an egg outside the nest is the stimulus that triggers the retrieval behavior.

It’s clear why this hardwired trait would be favored by natural selection. Goose mothers that retrieve their lost eggs are likely to have more surviving offspring, on average, than those that don’t.

However, this fixed action pattern can also occur under circumstances where it is not useful.

- If the egg that rolls out of the nest is picked up and taken away, the goose will keep moving her head as though pushing an imaginary egg.

- The goose will try to push any egg-shaped object, such as a golf ball, if it is placed near the nest. She’ll even carry out the retrieval pattern in response to a much larger object, such as a volleyball.

This example illustrates the fixed aspect of a fixed action pattern. In the great majority of cases a goose is likely to encounter in nature, the behavior of rolling any egg-like object near the nest back into the nest will be beneficial. However, it’s simply a biological program that runs in response to a stimulus and can have unhelpful results under unusual circumstances.

Male Sticklebacks

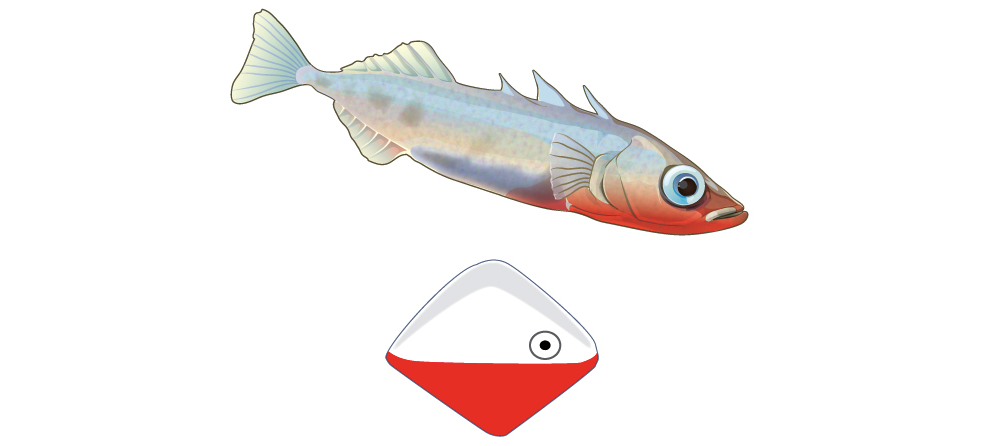

Another example of a fixed action pattern comes from the three-spined stickleback, a small freshwater fish. During the breeding season, male sticklebacks develop a red belly and display innate aggressive behavior towards other males.

When a male stickleback spots another nearby male, he will launch into a fixed action pattern involving aggressive displays designed to scare off the stranger. The specific stimulus that triggers this fixed action pattern is the red belly coloration pattern characteristic of males during breeding season.

Scientists establish this as the trigger through a lab experiment. Researchers exposed male fish to objects that were painted red on their lower halves but didn’t otherwise look like a fish, see below. The male stickleback responded aggressively to the objects just as if they were male sticklebacks. In contrast, no response was triggered by lifelike male stickleback models that were painted white.

How do we know if a behavior is innate?

By definition, an innate behavior is genetically built to an organisms rather than learned. To test if the behavior is innate, scientists observe whether an action is performed correctly by naive animals, animals that have not had a chance to learn the behavior by experience. For instance, this might involve raising young animals separate from adults or without stimuli that trigger the behavior.

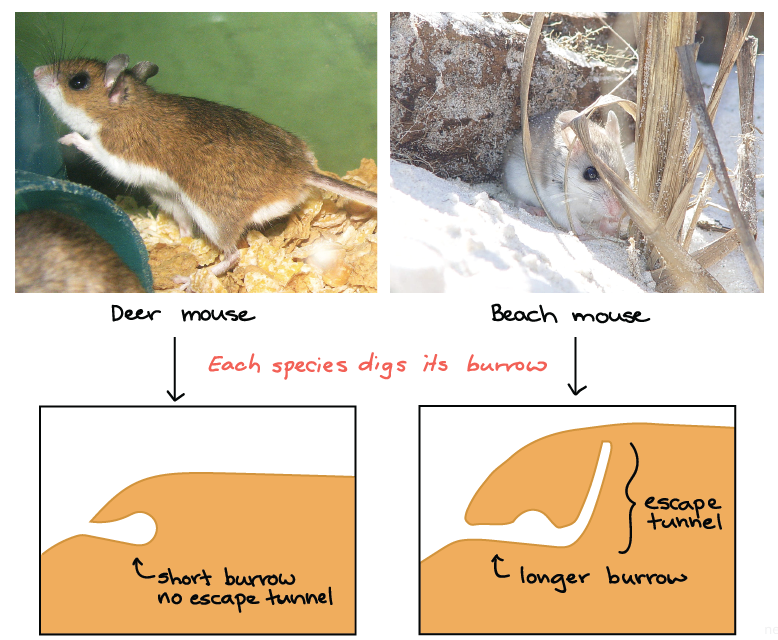

For example, let’s consider the digging behavior in the deer mouse and the beach mouse. These species are closely related and can interbreed, but they live in different natural environments and have different burrow-digging behaviors.

- The deer mouse digs a small, short burrow.

- The beach mouse digs a long burrow with an escape tunnel to get away from predators.

To test if this burrow digging is an innate behavior, researchers raised mice of both species in the lab with no exposure to sand or opportunity to burrow. Then, they provided them with sand, a cue for burrow constructions.

Given sand, each naive mouse dug exactly the type of burrow made by its species in the wild. That is, beach mice dug a long burrow with an escape tunnel, while deer mice dug a short burrow without an escape tunnel. The ability of the mice to construct their normal tunnels, without ever having seen such a tunnel before, showed that the burrowing behavior was innate.