Key Points

- According to the biological species concept, organisms belonging to the same species if they can interbreed to produce viable, fertile offspring.

- Species are separated from one another by prezygotic and postzygotic barriers, which prevent mating or the production of viable, fertile offspring.

- Speciation is the process new species form. It occurs when groups in a species become reproductively isolated and diverge.

- In allopatric speciation, groups from an ancestral population evolve into separate species due to a period of geological separation.

- In sympatric speciation, groups from the same ancestral population evolve into separate species without geographical separation.

Introduction

Organisms that look alike often belong to the same species, but this isn’t always the case. For example, an African fish eagles and the bald eagle are, in fact, different species, but are nearly identical.

Oppositely, organisms that belong to the same species can look very different from one another. For instance, dogs come in all shapes an sizes—from tiny Chihuahuas to massive Great Danes—but they all belong to the same species: Canis familiaris, the domestic dog.

To define a species, particularly in eukaryotes, scientists uses a species’ reproductive compatibility. Organisms are usually considered to be members of the same species if they can successfully reproduce with one another.

The Biological Species Concept

According to the most widely used species definition, the biological species concept, a is a group of organisms that can potentially interbreed, or mate, with one another to produce, viable, fertile offspring.

In this definition, members of the same species must have the potential to interbreed. However, that doesn’t mean that they have to be part of the same interbreeding group in real life. For example, a dog living in Australia and a dog living in Africa are unlikely to meet but could have puppies if they did.

In order o be considered a single species in the biological species concept, a group of organisms must produce healthy, fertile offspring when they interbreed. In some case, organisms of different species can mate and produce healthy offspring, but the offspring are infertile, can’t reproduce.

For instance, when a female horse and a male donkey mate, they produce a hybrid offspring called mules. Although a mule, pictured below, is perfectly healthy and can live to a ripe old age, it is infertile and cannot have its own offspring. Because of this, we consider horses and donkeys separate species.

The biological species concept connects the idea of a species to the process of evolution. Because members of a species can interbreed, the species as a whole has a common gene pool, a collection of gene variants.

On the other hand, genes are not exchanged between different species. Even if organisms of different species combine their DNA to make offspring, the offspring will be sterile, unable to pass on their genes. Because of this restricted gene flow, each species evolves as a group distinct from other species.

What keeps species distinct?

Broadly speaking, different species are unable to interbreed and produce healthy, fertile offspring due to barriers called mechanisms of reproductive isolation. These barriers can be split into two categories based on when they act: prezygotic and postzygotic.

Prezygotic Barriers

Prezygotic barriers prevent members of different species from mating to produce a zygote, a single-celled embryo. Some example scenarios are below:

- Two species might prefer different habitats and thus be unlikely to encounter one another. This is called habitat isolation.

- Two species might reproduce at different times of the day or year and thus be unlikely to meet up when seeking mates. This is called temporal isolation.

- Two species might have different courtship behaviors or mate preferences and thus find each other “unattractive”. This is known as behavioral isolation.

- Two species might produce egg and sperm cells that can’t combine in fertilization, even if they meet up through mating. This is known as gametic isolation.

- Two species might have bodies or reproductive structures that simply don’t fit together. This is called mechanical isolation.

These are all examples of prezygotic barriers because they prevent a hybrid zygote from ever forming.

Postzygotic Barriers

Postzygotic barriers keep hybrid zygotes—one-celled embryos with parents of two different species—from developing into healthy, fertile adults. Postzygotic barriers are often related to the hybrid embryo’s mixed set of chromosomes, which may not match up correctly or carry a complete set of information.

In some cases, the chromosomal mismatch is lethal to the embryo or results in an individual that can survive but is unhealthy. In other cases, a hybrid can survive to adulthood in good health but is infertile because it can’t split its mismatched chromosomes evenly into eggs and sperm. For example, this type of mismatch explains why mules are sterile, unable to reproduce

Prezygotic and postzygotic barriers not only keep species distinct, but also play a role in the formation of new species.

How do new species arise?

New species arise through a process called speciation. In speciation, an ancestral species splits into two or more descendant species that are genetically different from one another and can no longer interbreed.

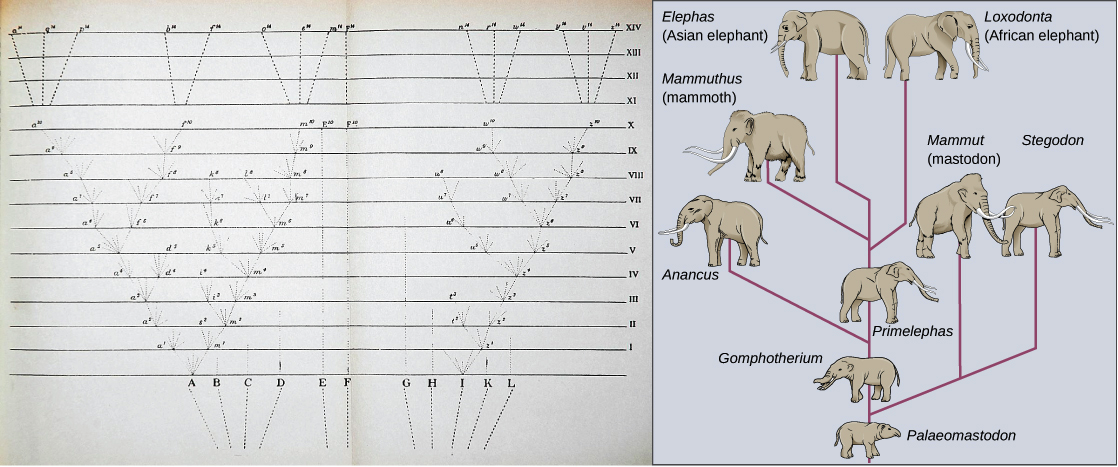

Darwin envisioned speciation as a branching event. In fact, he considered it so important that he depicted it in the only illustration of his famous book, On the Origin of Species, below left. A modern representation of Darwin’s idea is shown in the evolutionary tree of elephants and their relatives, below right, which reconstructs speciation events during the evolution of this group.

For speciation to occur, two new populations must be formed from one original population, and they must evolve in such a way that it becomes impossible for individuals from the two new populations to interbreed. Biologists often divide the ways that speciation can occur into two broad categories:

- Allopatric speciation—allo meaning other and patric meaning homeland—involves geographic separation of populations from a parent species and subsequent evolution.

- Sympatric speciation—sym meaning same and patric meaning homeland—involves speciation occurring within a parent species remaining in one location.

Allopatric Speciation

In allopatric speciation, organisms of an ancestral species evolve into two or more descendant species after a period of physical separation caused by a geographic barrier, such as a mountain range, rockslide, or river.

Sometimes barriers, such as a lava flow, split populations by changing the landscape. Other times, populations become separated after some members cross a pre-existing barrier. For example, members of a mainland population may become isolated on an island if they float over on a piece of debris.

Once the groups are reproductively isolated, they may undergo genetic divergence. That is, they may gradually become more and more different in their genetic makeup and heritable features over many generations. Genetic divergence happens because of natural selection, which may favor different traits in each environment, and other evolutionary forces like genetic drift.

As they diverge, the groups may evolve traits that act as prezygotic and/or postzygotic barriers to reproduction. For instance, if one group evolves large body size and the other evolves small body size, the organisms may not be physically able to mate—a prezygotic barrier—if the populations are reunited.

If the reproductive barriers that have arisen are strong—effectively preventing gene flow—the groups will keep evolving along separate paths. That is, they won’t exchange genes with one another even if the geographical barrier is removed. At this point, the groups can be considered separate species.

Case Study: Squirrels and the Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon was gradually carved out by the Colorado River over millions of years. Before it formed, only one species of squirrel inhabited the area. As the canyon got deeper over time, it became increasingly difficult for squirrels to travel between the north and south sides.

Eventually, the canyon became too deep for the squirrels to cross and a subgroup of squirrels became isolated on each side. Because the squirrels on the north and south sides were reproductively isolated from one another due to the deep canyon barrier, they eventually diverged into different species

Sympatric Speciation

In sympatric speciation, organisms from the same ancestral species become reproductively isolated and diverge without any physical separation.

There are several ways that sympatric speciation can happen. However, one mechanism that’s quite common—in plants, that is!—involves chromosome separation errors during cell division.

Polyploidy

Polyploidy is the condition of having more than two full sets of chromosomes. Unlike humans and other animals, plants are often tolerant of changes in their number of chromosome sets, and an increase in chromosome sets, a.k.a. ploidy, can be an instant recipe for plant sympatric speciation.

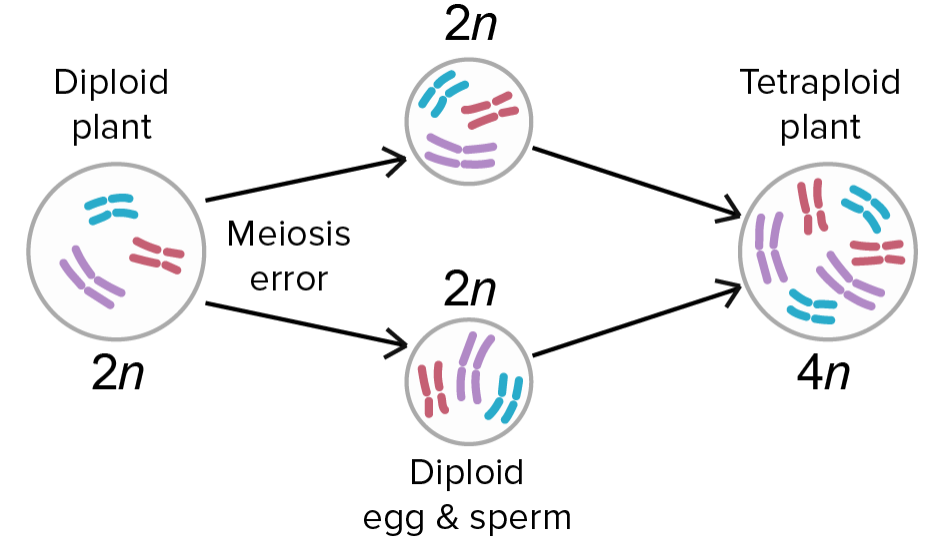

As an example, let’s consider the case where a tetraploid plant—4n, having four chromosome sets—suddenly pops up in a diploid population—2n, having two chromosome sets.

Such a tetraploid plant might arise if chromosome separation errors in meiosis produced a diploid egg and a diploid sperm that then met up to make a tetraploid zygote.

When the tetraploid plant matures, it will make diploid, 2n, eggs and sperm. These eggs and sperm can readily combine with other diploid eggs and sperm via self-fertilization, which is common in plants, to make more tetraploids.

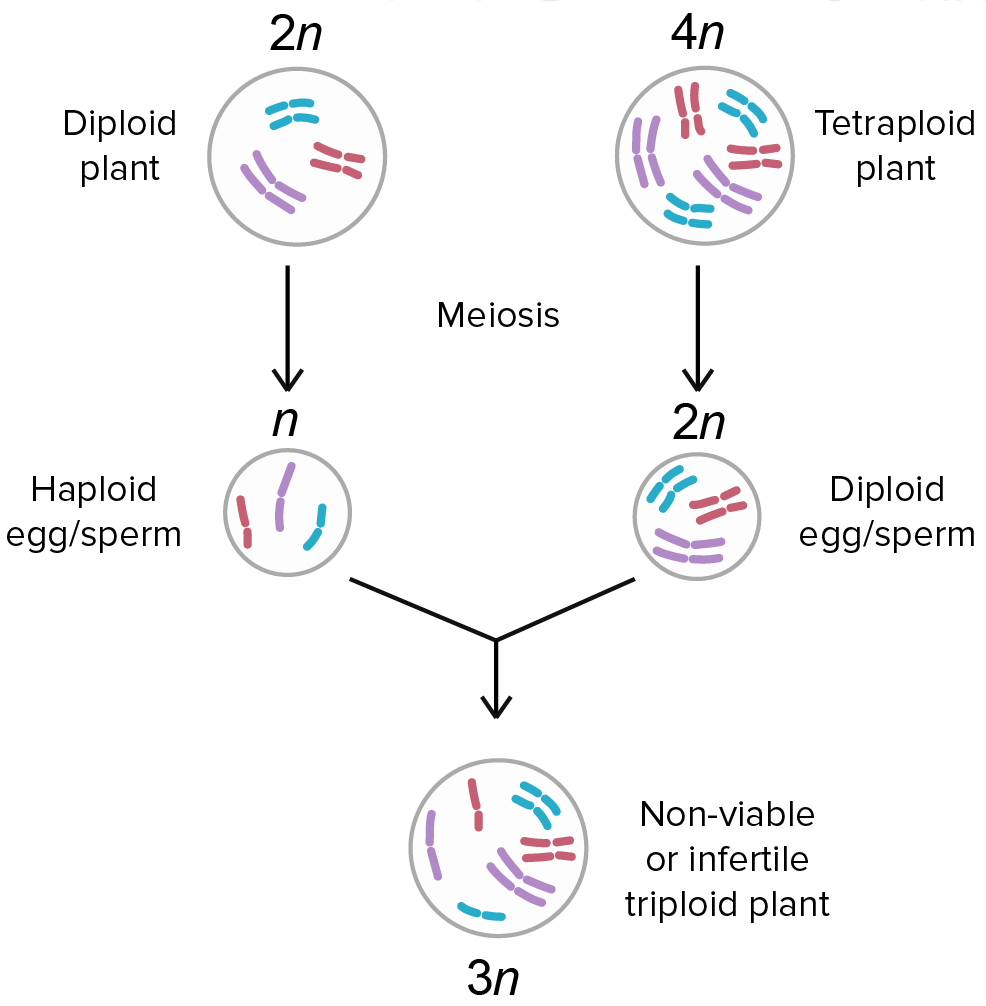

On the other hand, the diploid eggs and sperm may or may not combine effectively with the haploid, 1n, eggs and sperm from the parental species. Even if the diploid and haploid gametes do get together to produce a triploid plant with three chromosome sets, this plant would likely be sterile because its three chromosome sets could not pair up properly during meiosis.

Because the tetraploid plants and the diploid species from which they came cannot produce fertile offspring together, we consider them two separate species. This means that speciation occurred after just a single generation!

Speciation by polyploidy is common in plants but rare in animals. In general, animal species are much less likely to tolerate changes in ploidy. For instance, human embryos that are triploid or tetraploid are non-viable—they cannot survive.

Sympatric Speciation without Polyploidy

Can sympatric speciation, speciation without geographical separation, occur by mechanisms other than polyploidy? There’s some debate about how important or common a mechanism it is, but the answer appears to be yes, at least in some cases. For instance, sympatric speciation may take place when subgroups in a population use different habitats or resources, even though those habitats or resources are in the same geographical area.

One classic example is the North American apple maggot fly. As the name suggests, North American apple maggot flies, like the one pictured below, can feed and mate on apple trees. The original host plant of these flies, however, was the hawthorn tree. It was only when European settlers introduced apple trees about 200 years ago that some flies in the population started to exploit apples as a food source instead.

The flies that were born in apples tended to feed on apples and mate with other flies on apples, while the flies born on hawthorns tended to similarly stick with hawthorns. In this way, the population was effectively divided into two groups with limited gene flow between them, even though there was no reason an apple fly couldn’t go over to a hawthorne tree, or vice versa.

Over time, the population diverged into two genetically distinct groups with adaptations, features arising by natural selection, that were specific for apple and hawthorne fruits. For instance, the apple and hawthorne flies emerge at different times of year, and this genetically specified difference synchronizes them with the emergence date of the fruit on which they live.

Some interbreeding still occurs between the apple-specialized flies and the hawthorne-specialized flies, so they are not yet separate species. However, many scientists think this is a case of sympatric speciation in progress.