Sympatric speciation is a type of speciation where organisms from the same ancestral species become reproductively isolated and diverge without any physical separation.

There are several ways that sympatric speciation can happen. However, one mechanism that’s quite common—in plants, that is!—involves chromosome separation errors during cell division.

Polyploidy

Polyploidy is the condition of having more than two full sets of chromosomes. Unlike humans and other animals, plants are often tolerant of changes in their number of chromosome sets, and an increase in chromosome sets, a.k.a. ploidy, can be an instant recipe for plant sympatric speciation.

As an example, let’s consider the case where a tetraploid plant—4n, having four chromosome sets—suddenly pops up in a diploid population—2n, having two chromosome sets.

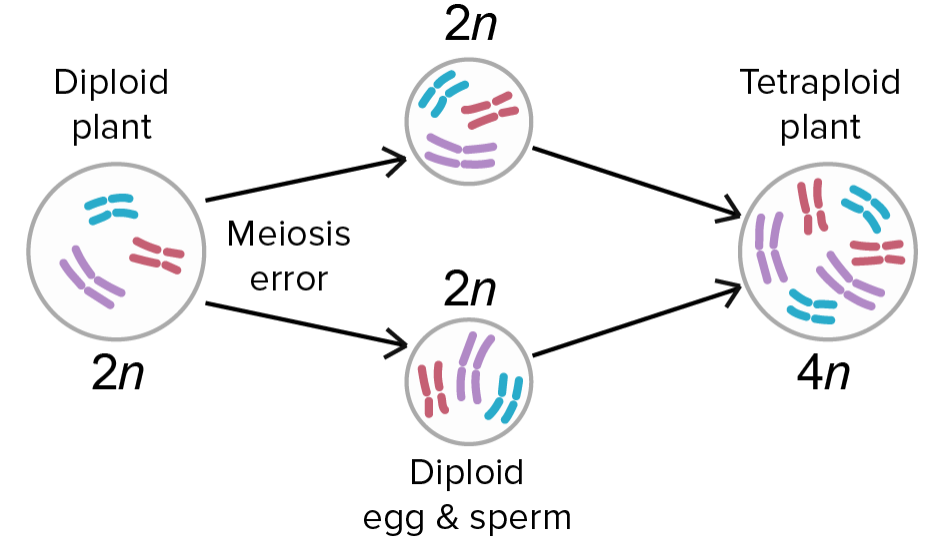

Such a tetraploid plant might arise if chromosome separation errors in meiosis produced a diploid egg and a diploid sperm that then met up to make a tetraploid zygote.

When the tetraploid plant matures, it will make diploid, 2n, eggs and sperm. These eggs and sperm can readily combine with other diploid eggs and sperm via self-fertilization, which is common in plants, to make more tetraploids.

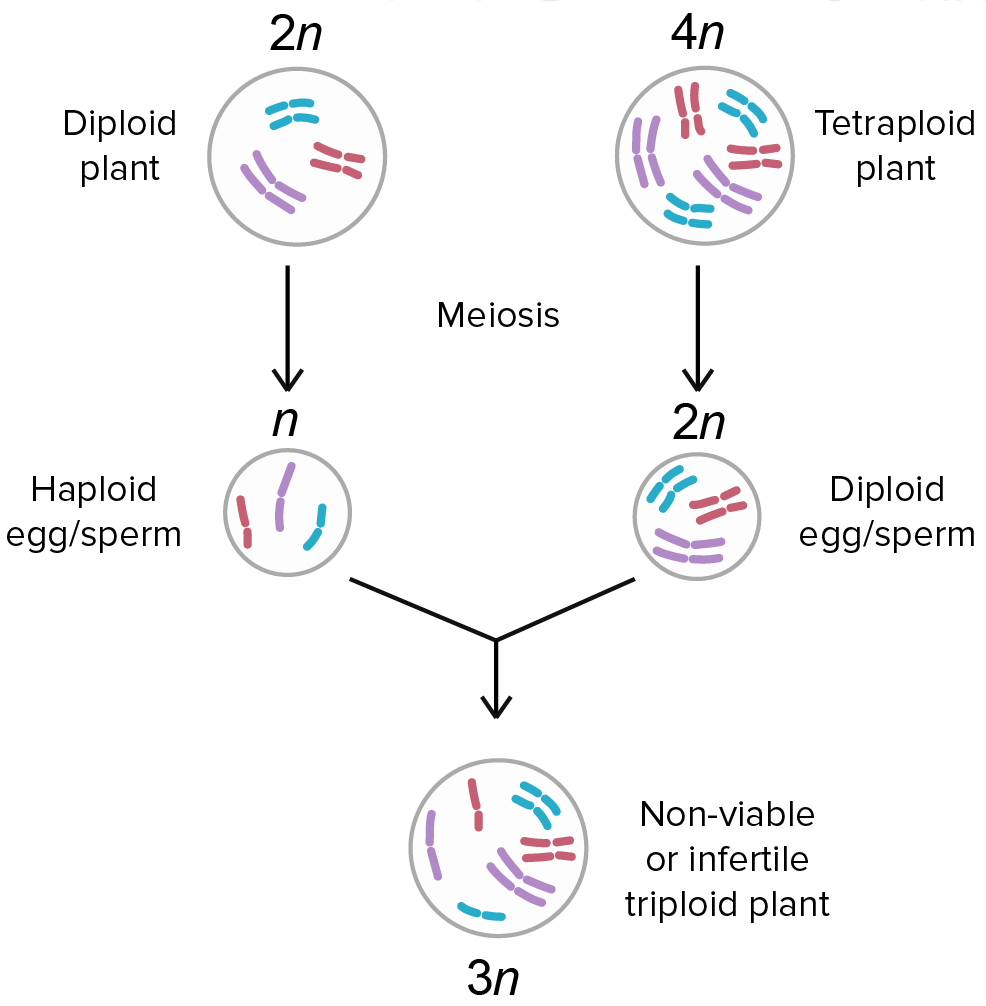

On the other hand, the diploid eggs and sperm may or may not combine effectively with the haploid, 1n, eggs and sperm from the parental species. Even if the diploid and haploid gametes do get together to produce a triploid plant with three chromosome sets, this plant would likely be sterile because its three chromosome sets could not pair up properly during meiosis.

Because the tetraploid plants and the diploid species from which they came cannot produce fertile offspring together, we consider them two separate species. This means that speciation occurred after just a single generation!

Speciation by polyploidy is common in plants but rare in animals. In general, animal species are much less likely to tolerate changes in ploidy. For instance, human embryos that are triploid or tetraploid are non-viable—they cannot survive.

Sympatric Speciation without Polyploidy

Can sympatric speciation, speciation without geographical separation, occur by mechanisms other than polyploidy? There’s some debate about how important or common a mechanism it is, but the answer appears to be yes, at least in some cases. For instance, sympatric speciation may take place when subgroups in a population use different habitats or resources, even though those habitats or resources are in the same geographical area.

One classic example is the North American apple maggot fly. As the name suggests, North American apple maggot flies, like the one pictured below, can feed and mate on apple trees. The original host plant of these flies, however, was the hawthorn tree. It was only when European settlers introduced apple trees about 200 years ago that some flies in the population started to exploit apples as a food source instead.

The flies that were born in apples tended to feed on apples and mate with other flies on apples, while the flies born on hawthorns tended to similarly stick with hawthorns. In this way, the population was effectively divided into two groups with limited gene flow between them, even though there was no reason an apple fly couldn’t go over to a hawthorne tree, or vice versa.

Over time, the population diverged into two genetically distinct groups with adaptations, features arising by natural selection, that were specific for apple and hawthorne fruits. For instance, the apple and hawthorne flies emerge at different times of year, and this genetically specified difference synchronizes them with the emergence date of the fruit on which they live.

Some interbreeding still occurs between the apple-specialized flies and the hawthorne-specialized flies, so they are not yet separate species. However, many scientists think this is a case of sympatric speciation in progress.