Negative feedback ccurs when some function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused by changes in the input or by other disturbances. A classic example of negative feedback is a heating system thermostat — when the temperature gets high enough, the heater is turned OFF. When the temperature gets too cold, the heat is turned back ON. In each case the “feedback” generated by the thermostat “negates” the trend. The opposite tendency — called positive feedback — is when a trend is positively reinforced, creating amplification.

Maintaining Homeostasis

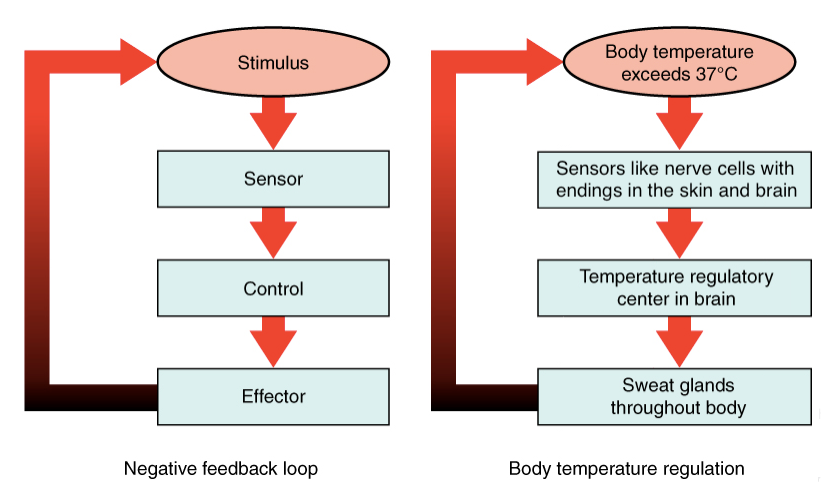

Maintenance of homeostasis usually involves negative feedback loops. These loops act to oppose the stimulus, or cue, that triggers them. For example, if your body temperature is too high, a negative feedback loop will act to bring it back down towards the set point, or target value, of /.

irst, high temperature will be detected by sensors—primarily nerve cells with endings in your skin and brain—and relayed to a temperature-regulatory control center in your brain. The control center will process the information and activate effectors—such as the sweat glands—whose job is to oppose the stimulus by bringing body temperature down.

In general, homeostatic circuits usually involve at least two negative feedback loops:

- One is activated when a parameter—like body temperature—is above the set point and is designed to bring it back down.

- One is activated when the parameter is below the set point and is designed to bring it back up.

Homeostasis depends on negative feedback loops. So, anything that interferes with the feedback mechanisms can—and usually will—disrupt homeostasis. In the case of the human body, this may lead to disease.