Plasmodesmata

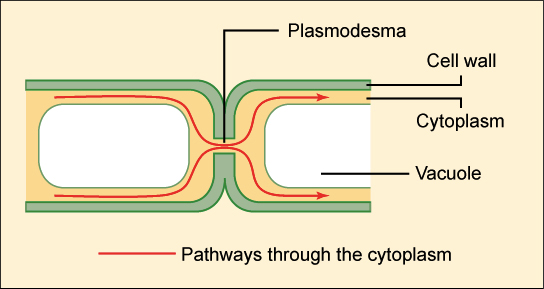

Plant cells, surrounded as they are by cell walls, don’t contact one another through wide stretches of plasma membrane the way animal cells can. However, they do have specialized junctions called plasmodesmata (singular, plasmodesma), places where a hole is punched in the cell wall to allow direct cytoplasmic exchange between two cells.

Plasmodesmata are lined with plasma membrane that is continuous with the membranes of the two cells. Each plasmodesma has a thread of cytoplasm extending through it, containing an even thinner thread of endoplasmic reticulum (not shown in the diagram above).

Molecules below a certain size (the size exclusion limit) move freely through the plasmodesmal channel by passive diffusion. The size exclusion limit varies among plants, and even among cell types within a plant. Plasmodesmata may selectively dilate (expand) to allow the passage of certain large molecules, such as proteins, although this process is poorly understood.

Gap Junctions

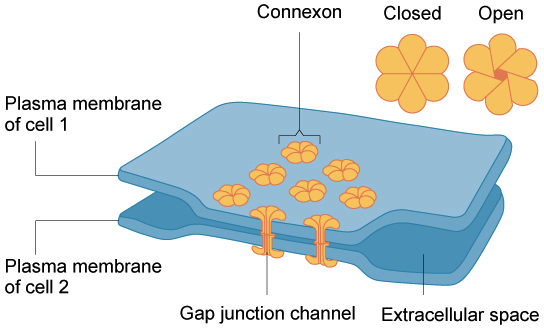

Functionally, gap junctions in animal cells are a lot like plasmodesmata in plant cells: they are channels between neighboring cells that allow for the transport of ions, water, and other substances. Structurally, however, gap junctions and plasmodesmata are quite different.

In vertebrates, gap junctions develop when a set of six membrane proteins called connexins form an elongated, donut-like structure called a connexon. When the pores, or “doughnut holes,” of connexons in adjacent animal cells align, a channel forms between the cells. (Invertebrates also form gap junctions in a similar way, but use a different set of proteins called innexins.)

Gap junctions are particularly important in cardiac muscle: the electrical signal to contract spreads rapidly between heart muscle cells as ions pass through gap junctions, allowing the cells to contract in tandem.

Tight Junctions

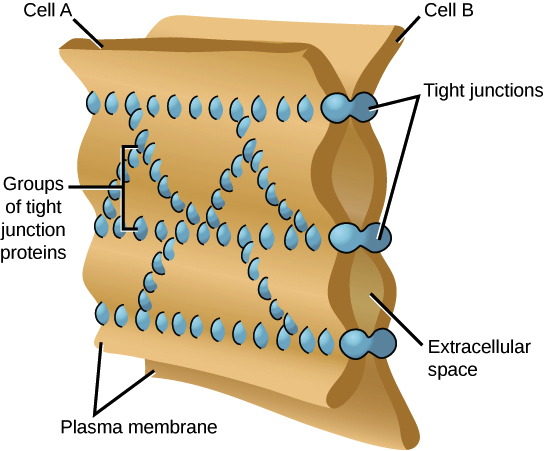

Not all junctions between cells produce cytoplasmic connections. Instead, tight junctions create a watertight seal between two adjacent animal cells.

At the site of a tight junction, cells are held tightly against each other by many individual groups of tight junction proteins called claudins, each of which interacts with a partner group on the opposite cell membrane. The groups are arranged into strands that form a branching network, with larger numbers of strands making for a tighter seal.

The purpose of tight junctions is to keep liquid from escaping between cells, allowing a layer of cells (for instance, those linings an organ) to act as an impermeable barrier. For example, the tight junctions between the epithelial cells lining your bladder prevent urine from leaking out into the extracellular space.

Desmosomes

Animal cells may also contain junctions called desmosomes, which act like spot welds between adjacent epithelial cells. A desmosome involves a complex of proteins. Some of these proteins extend across the membrane, while others anchor the junction within the cell.

Cadherins, specialized adhesion proteins, are found on the membranes of both cells and interact in the space between them, holding the membranes together. Inside the cell, the cadherins attach to a structure called the cytoplasmic plaque (red in the image at right), which connects to the intermediate filaments and helps anchor the junction.

Desmosomes pin adjacent cells together, ensuring that cells in organs and tissues that stretch, such as skin and cardiac muscle, remain connected in an unbroken sheet.