Key Points

- Genetic drift is a mechanism of evolution in which allele frequencies of a population change over generations due to change (sampling error).

- Genetic drift occurs in all populations of non-infinite size, but its effects are strongest in small populations.

- Genetic drift may result in the loss of some alleles (including beneficial ones) and the fixation, or rise to 100% frequency, of other alleles.

- Genetic drift can have major effect when a population is sharply reduced in size by a natural disaster or when a small group splits off from the main population to found a colony.

What is genetic drift?

Genetic drift is change in allele frequencies in a population from generation to generation that occurs due to change events. To be more exact, genetic drift is change due to “sampling error” in selecting the alleles for the next generation from the gene pool of the current generation. Although genetic drifts happen in populations of all sizes, its effect tend to be stronger in small populations.

Genetic Drift Example

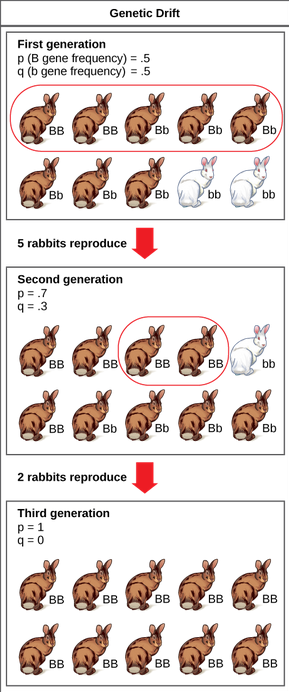

In the diagram below, we have a very small rabbit population that’s made up of 8 brown individuals (genotype bb). Initially, the frequencies of the B and b alleles are equal.

What if, purely by chance, only the 5 circled individuals in the rabbit population reproduce? In the surviving group, the frequency of the B allele is 0.7, and the frequency of the b allele is 0.3

In the example, the allele frequencies of the five lucky rabbits are perfectly represented in the second generation, as shown at right. Because the 5-rabbit “sample” in the previous generation had different allele frequencies than the population as a whole, frequencies of B and b in the population have shifted to 0.7 and 0.3, respectively.

Population Size Matters

Larger populations are unlikely to change this quickly as a result of genetic drift. For instance, if we followed a population of 1000 rabbits (instead of 10), it’s much less likely that the b allele would be lost ( and that the B allele would reach 100% frequency, or fixation) after such a short period of time. If only half of the 1000-rabbit population survived to reproduce, as in the first generation of the example above, the survive rabbits (500 of them) would tend to be a much more accurate representation of the allele frequencies of the original population - simply because the sample would be so much larger.

Allele benefit or harm doesn’t matter

Genetic drift, unlike natural selection, does not take into account an allele’s benefit (or harm) to the individual that carries it. That is, a beneficial allele may be lost, or a slightly harmful allele may become fixed, purely by chance.

A beneficial or harmful allele would be subject to selection as well as drift, but strong drift (for example, in a very small population) might still cause fixation of a harmful allele or loss of a beneficial one.

The Bottleneck Effect

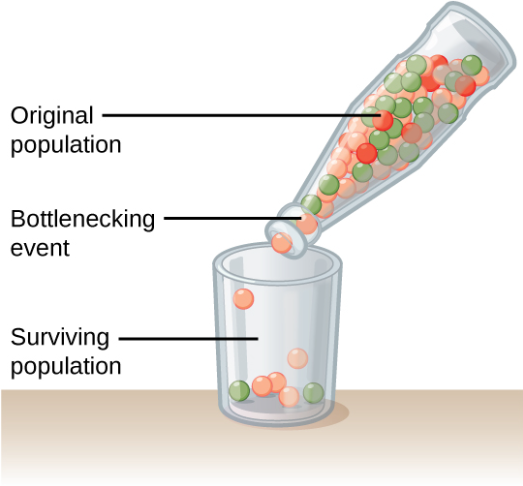

The bottleneck effect is an extreme example of genetic drift that happens when the size of a population is severely reduced. Events like natural disasters can decimate a population, killing most individuals and leaving behind a small, random assortment of survivors.

The allele frequencies in this group may be very different from those of the population prior to the event, and some alleles may be missing entirely. The smaller population will also be more susceptible to the effects of genetic drift for generations (until its numbers return to normal), potentially causing even more alleles to be lost.

The Founder Effect

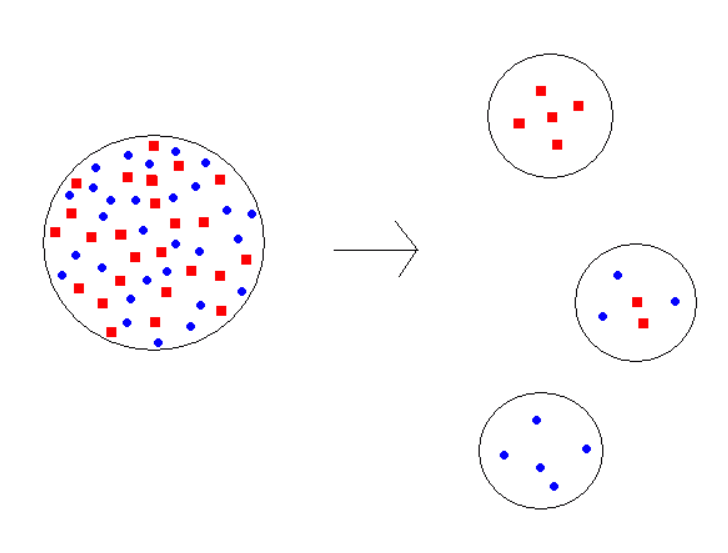

The founder effect is another extreme example of drift, one that occurs when a small group of individuals breaks off from a larger population to establish a colony. The new colony is isolated from the original population, and the founding individuals may not represent the full genetic diversity of the original population. That is, alleles in the founding population may be present at different frequencies than in the original population, and some alleles may be missing altogether. The founder effect is similar in concept to the bottleneck effect, but it occurs via a different mechanism.

In the figure above, you can see a population made up of equal numbers of squares and circles (assuming an individual’s shape is determined by its alleles for a particular gene).

Random groups that depart to establish new colonies are likely to contain different frequencies of squares and circles than the original population. So, the allele frequencies in the colonies (small circles) may be different relative to the original population. Also, the small size of the new colonies means they will experience strong genetic drift for generations.

Summary

Unlike natural selection, genetic drift does not depend on an allele’s beneficial or harmful effects. Instead, drift changes allele frequencies purely by chance, as random subsets of individuals (and the gametes of those individuals) are sampled to produce the next generation.

Every population experiences genetic drift, but small populations feel its effects more strongly. Genetic drift does not take into account an allele’s adaptive value to a population, and it may result in loss of a beneficial allele or fixation (rise to frequency) of a harmful allele in a population.

The founder effect and the bottleneck effect are cases in which a small population is formed from a larger population. These “sampled” populations often do not represent the genetic diversity of the original population, and their small size means they may experience strong drift for generations.