Polyploidy is the condition of having more than two full sets of chromosomes. Unlike humans and other animals, plants are often tolerant of changes in their number of chromosome sets, and an increase in chromosome sets, a.k.a. ploidy, can be an instant recipe for plant sympatric speciation.

As an example, let’s consider the case where a tetraploid plant—4n, having four chromosome sets—suddenly pops up in a diploid population—2n, having two chromosome sets.

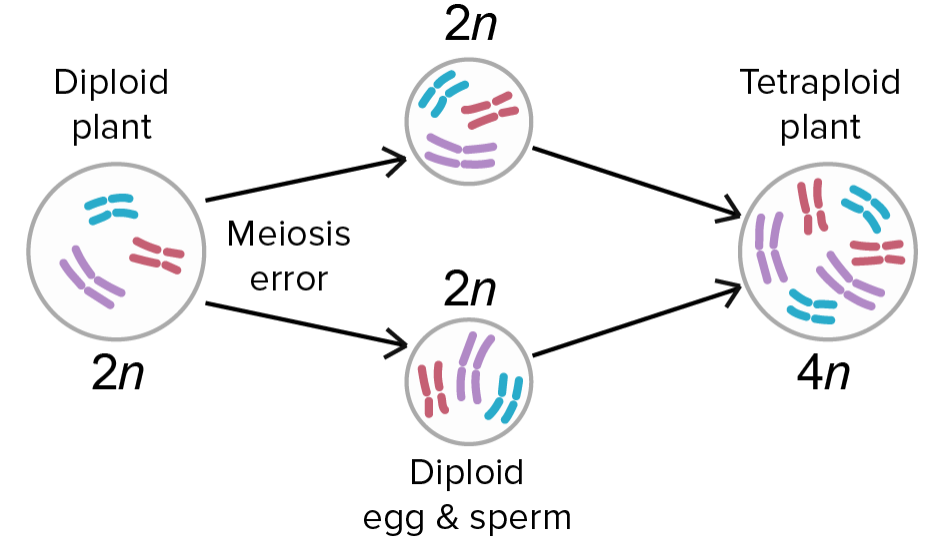

Such a tetraploid plant might arise if chromosome separation errors in meiosis produced a diploid egg and a diploid sperm that then met up to make a tetraploid zygote.

When the tetraploid plant matures, it will make diploid, 2n, eggs and sperm. These eggs and sperm can readily combine with other diploid eggs and sperm via self-fertilization, which is common in plants, to make more tetraploids.

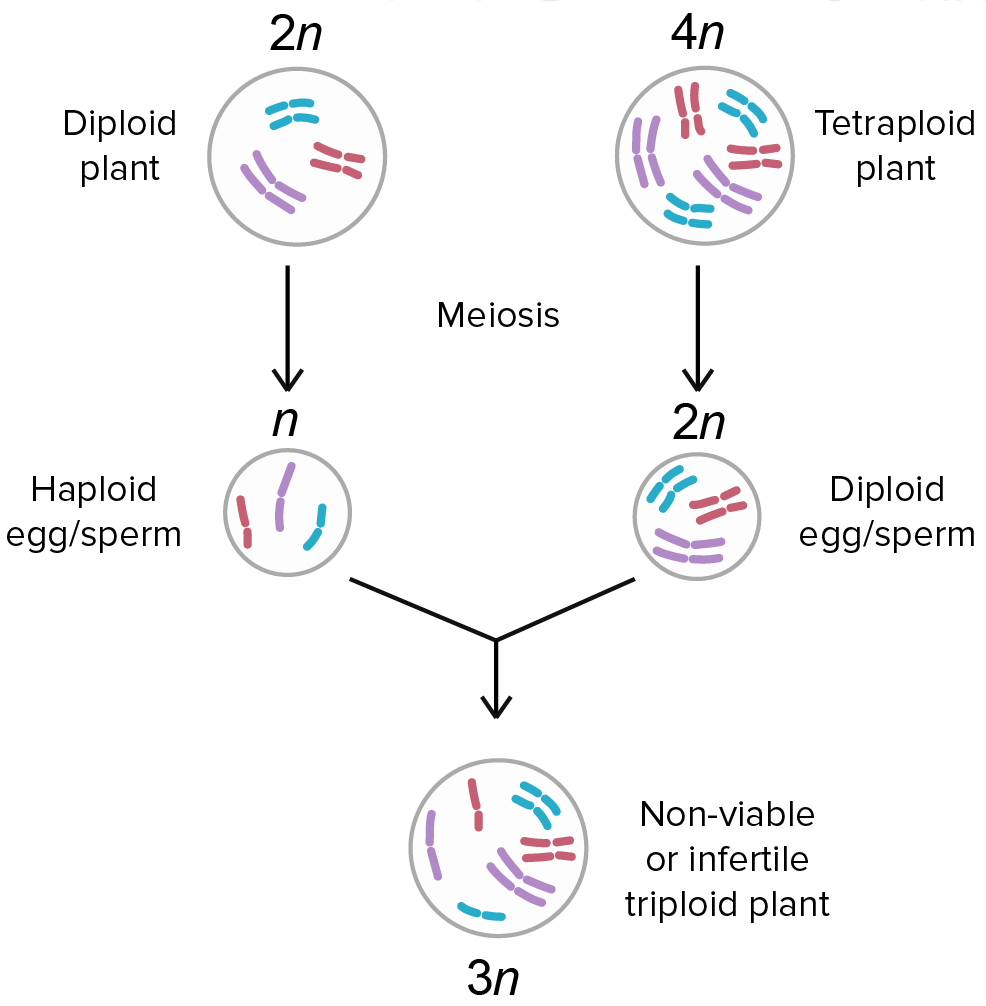

On the other hand, the diploid eggs and sperm may or may not combine effectively with the haploid, 1n, eggs and sperm from the parental species. Even if the diploid and haploid gametes do get together to produce a triploid plant with three chromosome sets, this plant would likely be sterile because its three chromosome sets could not pair up properly during meiosis.

Because the tetraploid plants and the diploid species from which they came cannot produce fertile offspring together, we consider them two separate species. This means that speciation occurred after just a single generation!

Speciation by polyploidy is common in plants but rare in animals. In general, animal species are much less likely to tolerate changes in ploidy. For instance, human embryos that are triploid or tetraploid are non-viable—they cannot survive.