Key Points

- Natural selection can cause microevolution (change in allele frequencies), with fitness-increasing alleles becoming more common in the population.

- Fitness is a measure of reproductive success (how many offspring an organisms leaves in the next generation, relative to others in the group).

- Natural selection can act on traits determined by alternative alleles of a single gene, or on polygenic traits (traits determined by many genes).

- Natural selection on traits determined by multiple genes may take the form of stabilizing selection, directional selection, or disruptive selection.

Natural selection can cause microevolution

Natural selection acts on an organism’s phenotype, or observable features. Phenotype is often largely a product of genotype (the alleles, or gene versions, the organism carries). When a phenotype produced by certain alleles helps organisms survive and reproduce better than their peers, natural selection can increase the frequency of the helpful alleles from one generation to the next - that is, it can cause microevolution.

Example: Rabbit Coat Color

As an example, let’s imagine a population of brown and white rabbits, whose coat color is determined by dominant brown (B) and recessive white (b) alleles of a single gene. If a predator such as a hawk can see white rabbits (genotype bb) more easily than brown rabbits (BB and Bb) against the backdrop of a grassy field, brown rabbits are more likely than white rabbits to survive hawk predation. Because more brown than white rabbits will survive to reproduce, the next generation will probably contain a higher frequency of B alleles.

In this example, the frequency of the survival-promoting B allele rose from 0.3 to 0.4 in a single generation. The percent of the population will be survival-promoting brown phenotype also rose from 50% to 65%. (We can predict the next generation by assuming that the survivors mate randomly and leave equal numbers of offspring an average).

Fitness = Reproductive Success

The phenotypes and genotypes favored by natural selection aren’t necessarily just the ones that survive best. Instead, they’re the ones with the highest overall fitness. Fitness is a measure of how well organisms survive and reproduce, with emphasis on “reproduce.” Officially, fitness is defined as the number of offspring that organisms with a particular genotype or phenotype leave behind, on average, as compared to others in the population.

Survival is one important component of fitness. In order to leave any offspring at all in the next generation, an organisms has to reach reproductive age. For instance, in the example above, brown rabbits had higher fitness than white rabbits, because a larger fraction of brown rabbits than white rabbits survived to reproduce. Living for a longer period of time may also allow an organisms to reproduce more separate times )e.g., with more mates or in multiple years).

However, survival is not the only part of the fitness equation. Fitness also depends on the ability to attract a mate and the number of offspring produced per mating. An organisms that survived for many years, but never successfully attracted a mate or had offspring, would have very (zero) low fitness.

Fitness Depends on the Environment

Which traits are favored by natural selection (that is, which features make an organism more fit) depends on the environment. For example, a brown rabbit might be more fit than a white rabbit in a brownish, grassy landscape with sharp-eyed predators. However, in a light-colored landscapes, white rabbits might be better than brown rabbits at avoiding predators. And if there weren’t any predators, the two coat colors might be equally fit.

In many cases, a trait also involves tradeoffs. That is, it may have some positive and negative effects on fitness. For instance, a particular coat color might make a rabbit less visible to predators, but also less attractive to potential mates. Since fitness is a function of both survival and reproduction, whether the coat color is a net “win” will depend on the relative strengths of the predation and the mat preference.

Natural selection can act on traits controlled by many genes

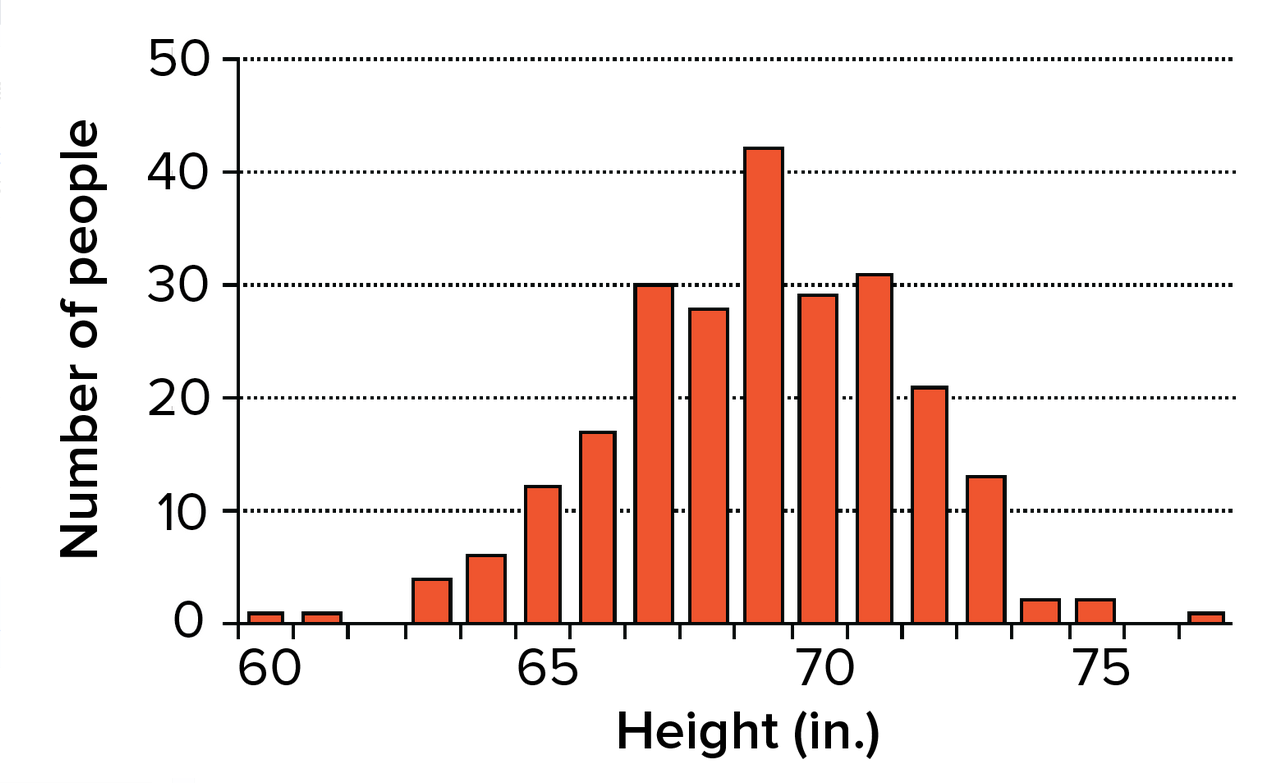

In some cases, different phenotypes in a population are determined by just one gene. However, in many cases, phenotypes are controlled by multiple genes that each make a small contribution overall result. Such phenotype are often called polygenic traits, and they typically form a spectrum, taking many slightly different forms. Plotting the frequency of the different forms in a population often results in a graph with a bell curve shape. Height (see graph below) and many other traits in humans are polygenic.

We can see if natural selection is acting on a polygenic trait by watching how the distribution of phenotypes in the population changes over tie. Certain characteristics shifts tell us selection is occurring, even if we don’t know exactly which genes control the trait.

How natural selection can shift genotype distribution

There are three basic ways that natural selection can influence distribution of phenotypes for polygenic traits in a population. To illustrate these forms of selection, let’s use an imaginary beetle population, in which beetle color is controlled by many genes and varies in a spectrum from light to dark green.

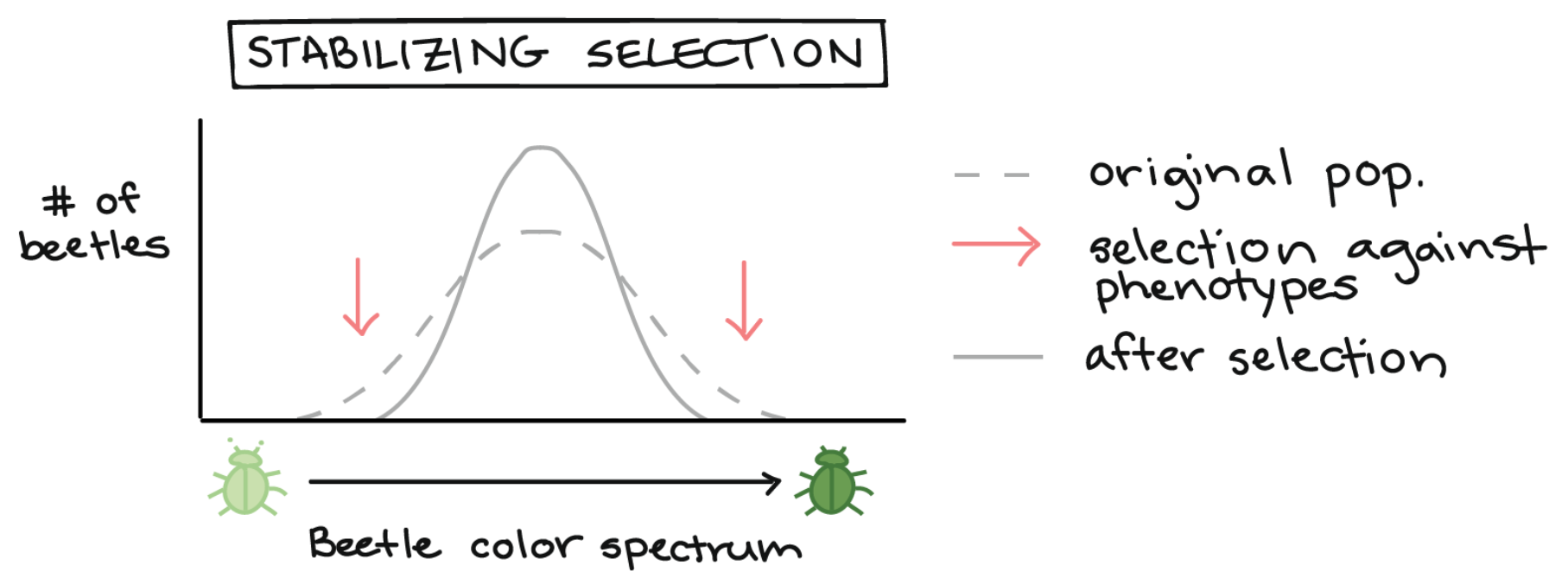

- Stabilizing selection. In stabilizing selection, intermediate phenotypes are more fit than extreme ones. For example, medium-green beetles might be the best camouflaged, and thus survive best, on a forest floor covered by medium-green plants. Stabilizing selection tends to narrow the curve.

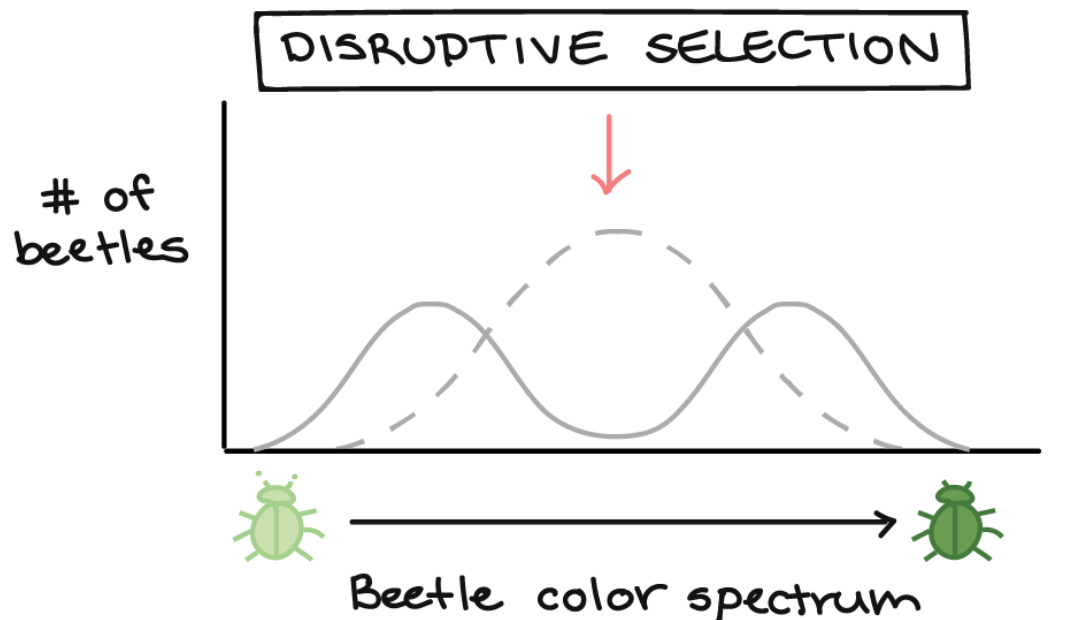

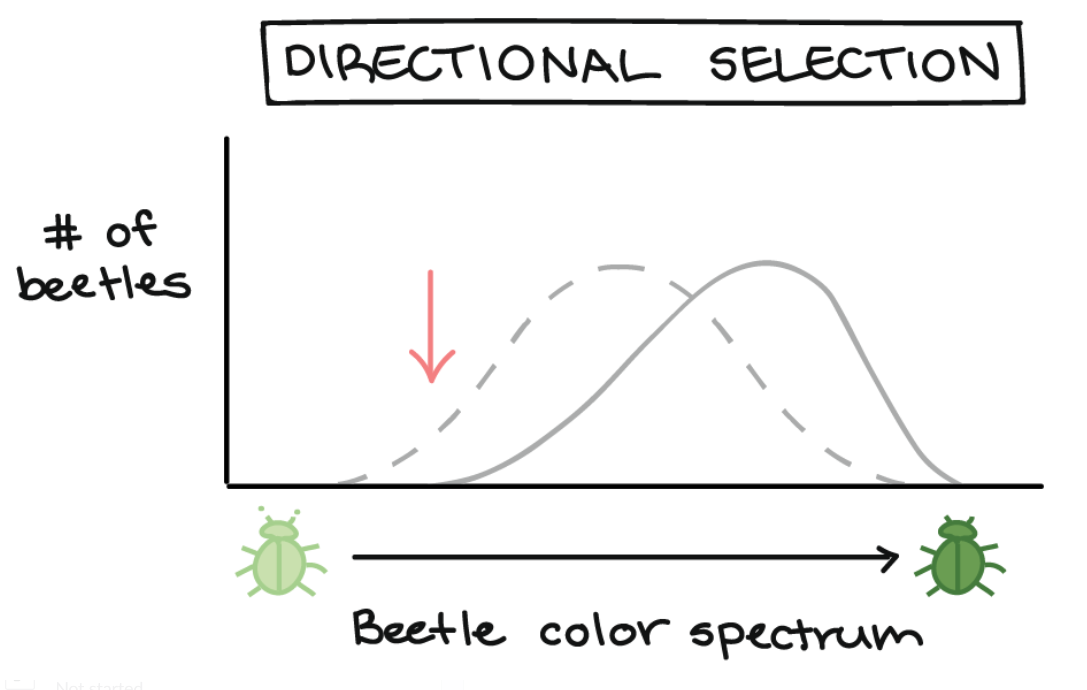

- Directional selection. One extreme phenotype is more fit than all the other phenotypes. For example, if the beetle population moves into a new environment with dark soil and vegetation, the dark green beetles might be better hidden and survive better than medium or light beetles. Directional selection shifts the curve towards the favorable phenotype.

- Disruptive selection. Both extreme phenotypes are more fit than those in the middle. For example, if the beetles move into a new environment with patches of light-green moss and dark-green shrubs, both light and dark beetles might be better hidden (and survive better) than medium-green beetles. Diversifying selection makes multiple peaks in the curve.