DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part of biological inheritance. This is essential for cell division during growth and repair of damaged tissues, while it also ensures that each of the new cells receives its own copy of the DNA.

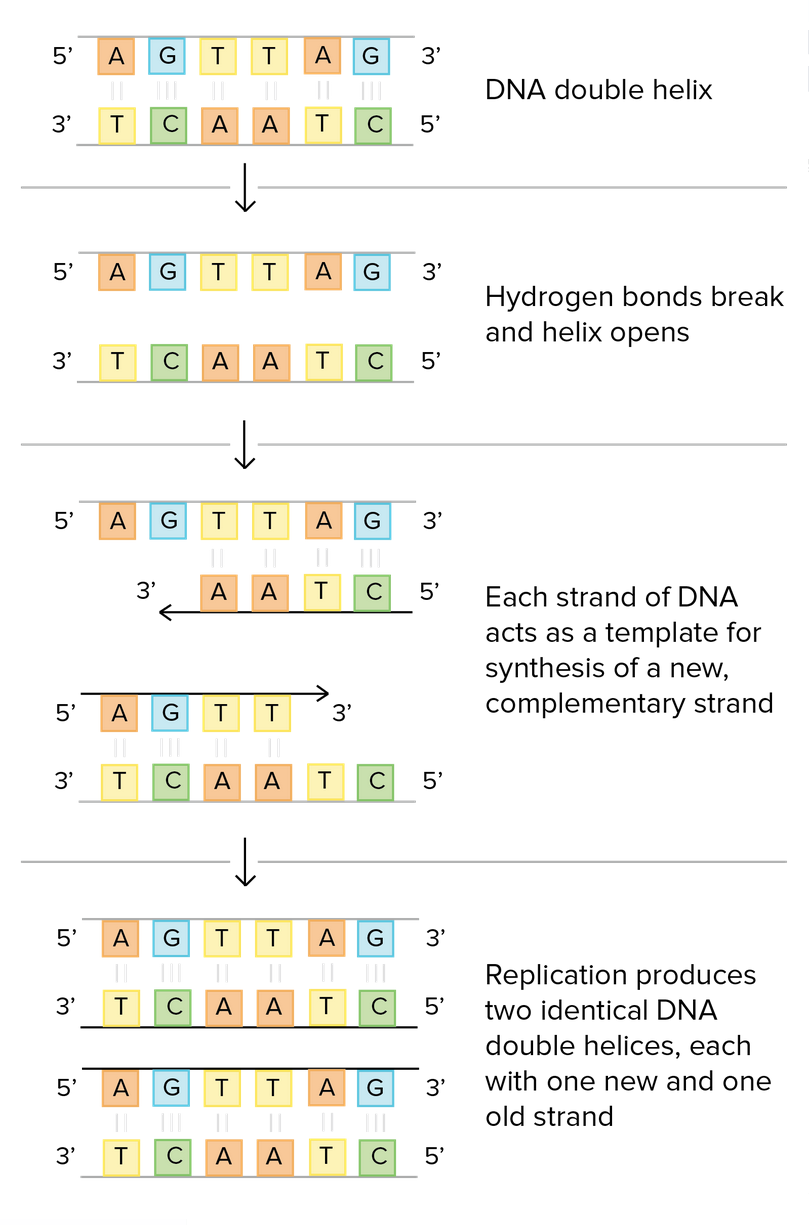

Basic Idea DNA replication is semiconservative. Each strand in the double helix acts as a template for synthesis of a new, complementary strand. This process takes us from one starting molecule to two “daughter” molecule with each newly formed double helix containing one new and one old strand.

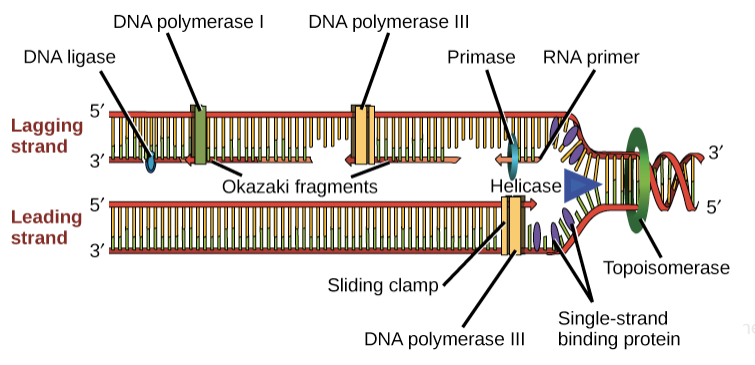

Cells need to copy their DNA very quickly, and with very few errors (or risk problems such as cancer). To do so, they use a variety of enzymes and proteins, which work together to make sure DNA replication is performed smoothly and accurately.

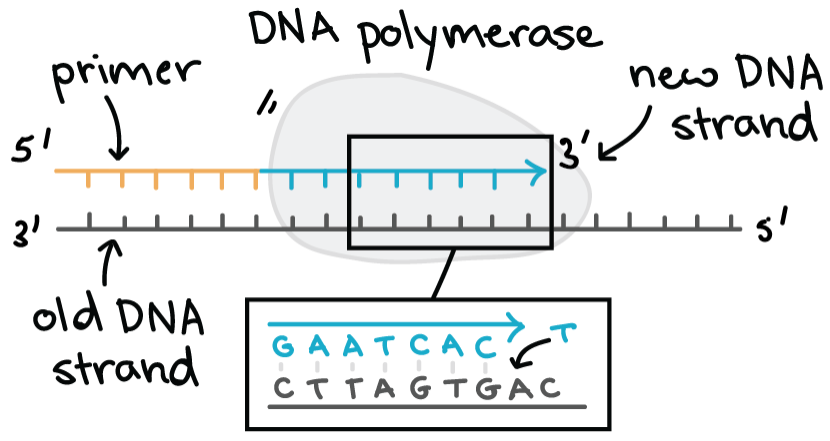

DNA Polymerase DNA polymerases are responsible for synthesizing DNA: they add nucleotides one by one to the growing DNA chain, incorporating only those that are complementary to the template.

Key features of DNA polymerases:

- They always need a template

- They can only add nucleotides to the 3’ end of the DNA strand

- They can’t start making a DNA chain from scratch, but require a pre-existing chain or short stretch of nucleotides called an RNA primer

- They proofread removing the vast majority of “wrong” nucleotides that are accidentally added to the chain.

The addition of nucleotides requires energy. This energy comes from the nucleotides themselves, which have three phosphates attached to them (much like the energy-carrying molecule ATP). When the bond between phosphates is broken, the energy released is used to form a bond between the incoming nucleotide and the growing chain.

In prokaryotes, there are two main DNA polymerases involved in DNA replication: DNA polymerase III (the major DNA-maker), and DNA Polymerase I, which plays a supporting role.

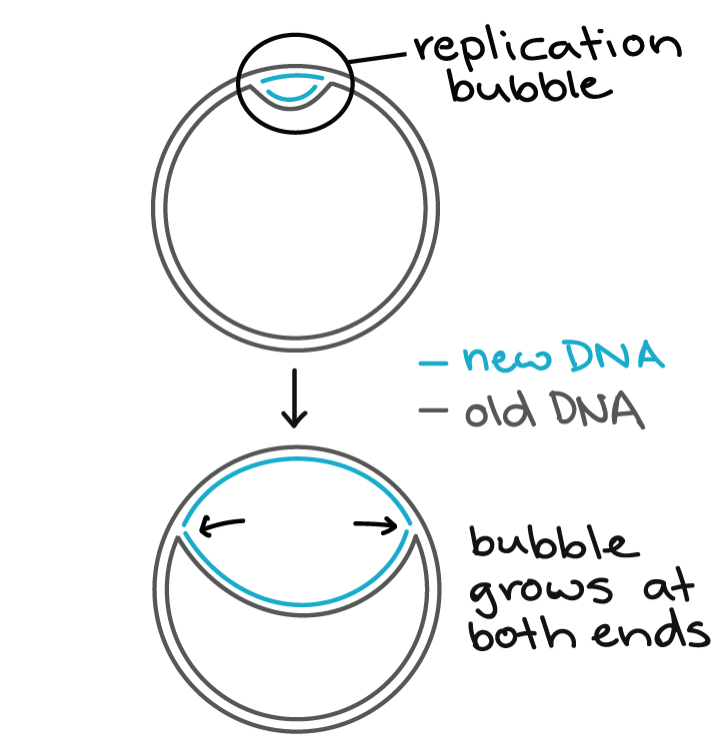

Starting DNA Replication Replication always starts at specific locations on the DNA, which are called origins of replication and recognized by their sequence.

Most bacteria have a single origin of replication on its chromosome. The origin is about 245 base pairs long and has mostly A/T base pairs (which are held together by fewer hydrogen bonds than G/C base pairs), making the DNA strands easier to separate.

Specialized proteins recognize the origin, bind to this site, and open up the DNA. As the DNA opens, two Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed, together making up what’s called a replication bubble. The replication forks will move in opposite directions as replication proceeds.

DNA Helicase is the first replication enzyme to load on at the origin of replication. Helicase’s job is to move the replication forks forward by “unwinding” the DNA (breaking the hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous base pairs).

Proteins called single-strand binding proteins coat the separated strands of DNA near the replication fork, keeping them from coming back together into a double helix.

Primers and Primase DNA polymerases can only add nucleotides to the 3’ end of a existing DNA strand. They use the free -OH group found at the 3’ end as a “hook,” adding a nucleotide to this group in the polymerization reaction. They cannot add the first nucleotide at a new replication fork alone.

They are helped by an enzyme called DNA primase. Primase makes an RNA primer, or a short stretch of nucleic acid complementary to the template, that provides a 3’ end for DNA polymerase to work on. A typical RNA primer is about five to ten nucleotides long. The RNA primer primes DNA synthesis, i.e., gets it started.

Once the RNA primer is in place, DNA polymerase “extends” it, adding nucleotides one by one to make a new DNA strand that’s complementary to the template strand.

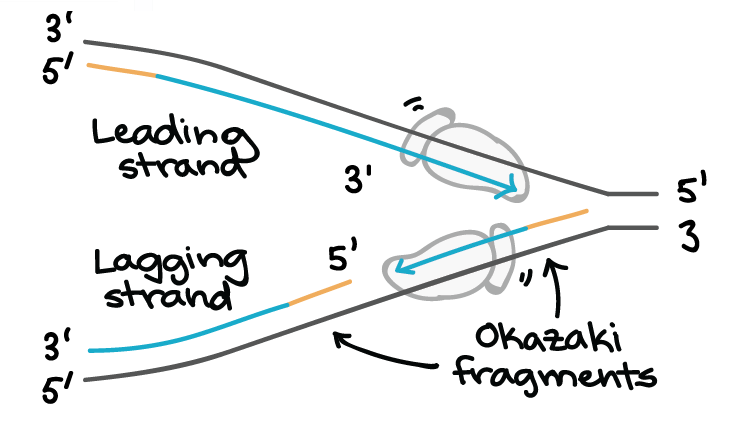

Leading and Lagging Strands In E. coli, the DNA polymerase that handles most of the synthesis is DNA polymerase III. There are two molecules of DNA polymerase III at a replication fork, each of them hard at work on one of the two DNA strands.

DNA polymerases can only make DNA in the 5’ to 3’ direction, and this poses a problem during replication. A DNA double helix is always anti-parallel (one strand runs in the 5’ to 3’ direction, while the other strand runs in the 3’ to 5’ direction). This makes it necessary for the two new strands, which are also antiparallel to their templates, to be made in slightly different ways.

One new strand, which runs 5’ to 3’ towards the replication fork, is the easy one. This strand is made continuously, because the DNA polymerase is moving in the same direction as the replication fork. This continuous synthesized strand is called the leading strand.

The other new strand, which runs 5’ to 3’ away from the fork, is trickier. This strand is made in fragments because, as the fork moves forward, the DNA polymerase (which is moving away from the fork) must come off and reattach on the newly exposed DNA. This tricky strand, which is made in Okazaki fragments, is called the lagging strand.

The leading strand can be extended from one RNA primer alone, whereas the lagging strand needs a new primer for each of the short Okazaki fragments.

The Maintenance and Cleanup Crew Some other proteins and enzymes, in addition the main ones above, are needed to keep DNA replication running smoothly. One is a protein called the sliding clamp, which holds DNA polymerase III molecules in place as they synthesize DNA. The sliding clamp is a ring-shaped protein and keeps the DNA polymerase of the lagging strand from floating off when it re-starts at a new Okazaki fragment.

DNA Topoisomerase also plays an important maintenance role during DNA replication. This enzyme prevents the DNA double helix ahead of the replication fork from getting too tightly wound as the DNA is opened up. It acts by making temporary nicks in the helix to release the tension, then sealing the nicks to avoid permanent damage.

Finally, there is a little cleanup work to do if we want DNA that doesn’t contain any RNA or gaps. The RNA primers are removed and replaced by DNA through the activity of DNA polymerase I, the other polymerase involved in replication. The nicks that remain after the primers are replaced and sealed by the enzyme DNA ligase.

Summary of DNA Replication in E. Coli

- DNA helicase opens up the DNA at the replication fork

- Single-strand binding proteins coat the DNA around the replication fork to prevent rewinding of the DNA

- DNA topoisomerase works at the region ahead of the replication fork to prevent super coiling

- DNA primase synthesizes RNA primers complementary to the DNA strand

- DNA polymerase III extends the RNA primers, adding on to the 3’ end, to make the bulk of the new DNA

- RNA primers are removed with DNA by DNA polymerase I

- The gaps between DNA fragments are sealed by DNA ligase

DNA Replication in Eukaryotes The basics of DNA replication is similar between bacteria and eukaryotes such as humans, but there are some differences.

- Eukaryotes usually have multiple linear chromosomes, each with multiple origins of replication. Humans can have up to 100000 origins of replication.

- Most of the E. coli enzymes have counterparts in eukaryotic DNA replication, but a single enzyme in E. coli may be represented by multiple enzymes in eukaryotes. For instance, there are five human DNA polymerases with important roles in replication.

- Most eukaryotic chromosomes are linear. Because of the way the lagging strand is made, some DNA is lost from the ends of linear chromosomes (the telomeres) in each round of replication.