LO: I can analyze the pros and cons of different biotechnology techniques.

Team 1: Gel Electrophoresis Gel electrophoresis is a technique used to separate DNA fragments (or other macromolecules, such as RNA and proteins) based on their size and charge. Electrophoresis involves running a current through a gel containing the molecules of interest. Based on their size and charge, the molecules will travel through the gel in different directions or at different speeds, allowing them to be separated from one another.

All DNA molecules have the same amount of charge per mass. Because of this, gel electrophoresis of DNA fragments separates them based on size only. Using electrophoresis, we can see how many different DNA fragments are present in a sample and how large they are relative to one another. We can also determine the absolute size of a piece of DNA by examining it next to a standard “yardstick” made up of DNA fragments of known sizes.

What is a gel? As the name suggests, gel electrophoresis involves a gel: a slab of Jello-like material. Gels for DNA separation are often made out of a polysaccharide called agarose, which comes as dry, powdered flakes. When the agarose is heated in a buffer (water with some salts in it) and allowed to cool, it will form a solid, slightly squishy gel. At the molecular level, the gel is a matrix of agarose molecules that are held together by hydrogen bonds and form tiny pores.

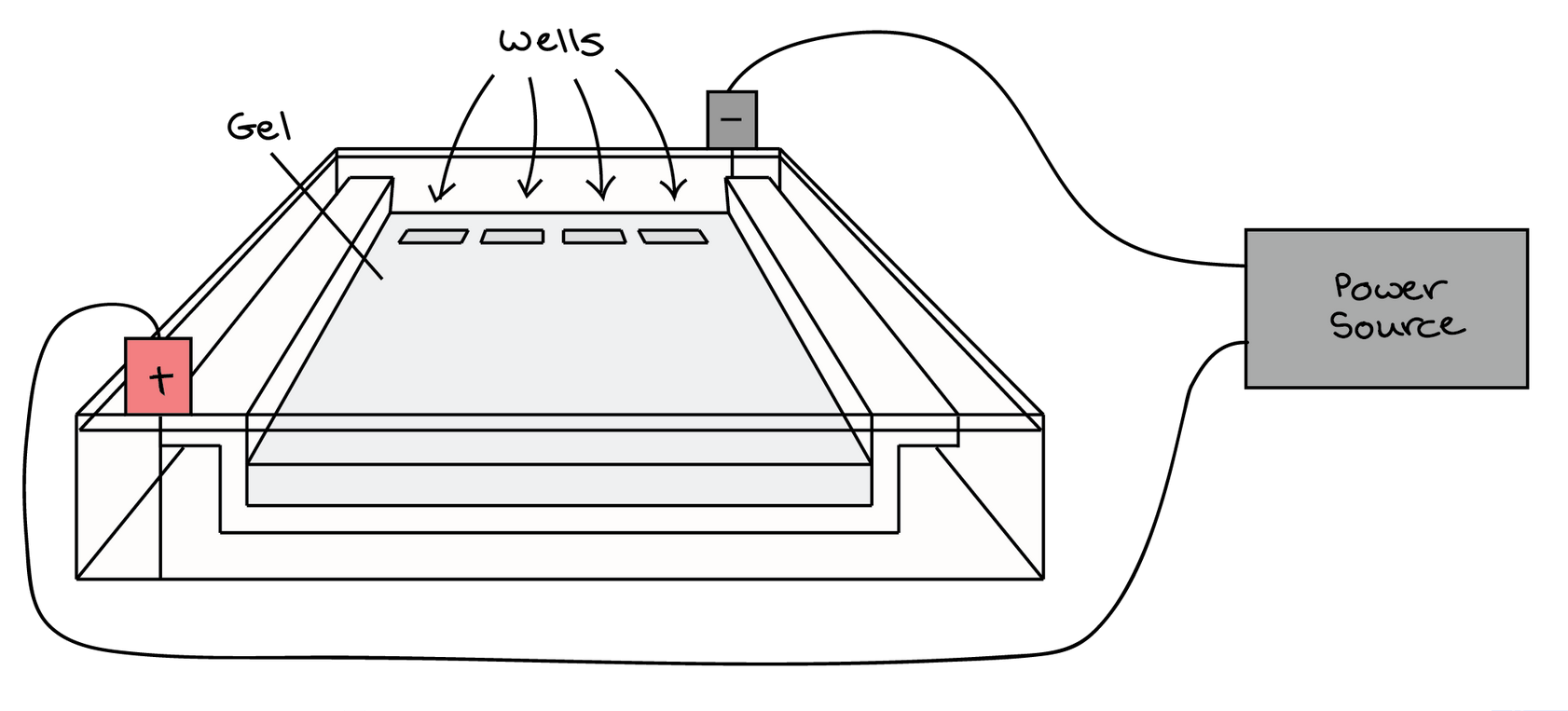

At one end, the gel has pocket-like indentations called wells, which are where the DNA samples will be placed:

Before the DNA samples are added, the gel must be placed in a gel box. One end of the box is hooked to a positive electrode, while the other end is hooked to a negative electrode. The main body of the box, where the gel is placed, is filled with a salt-containing buffer solution that can conduct current. Although you may not be able to see in the image above, the buffer fills the gel box to a level where it barely covers the gel.

The end of the gel with the wall is positioned towards the negative electrode. The end without wells (towards which the DNA fragments will migrate) is positioned towards the positive electrode.

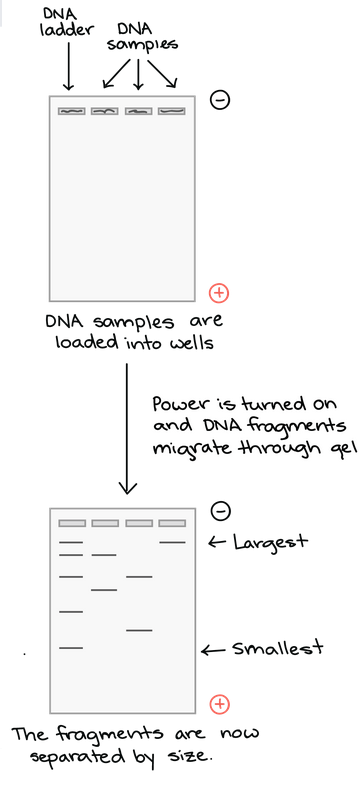

How do DNA fragments move through the gel? Once the gel is in the box, each of the DNA samples we want to examine (for instance, each PCR reaction or each restriction-digested plasmid) is carefully transferred into one of the wells. One well is reserved for a DNA ladder, a standard reference that contains fragments for known lengths. Commercial DNA ladders come in different size ranges, so we want to pick one with good “coverage” of the size range of our expected fragments.

Next, the power of the gel box is turned on, and the current begins to flow through the gel. The DNA molecules have a negative charge because of the phosphate groups in their sugar-phosphate backbone, so they start moving through the matrix of the gel towards the positive pole. When the power is turned on and current is passing through the gel, the gel is said to be running.

As the gel runs, shorter pieces of DNA will travel through the pores of the gel matrix faster than longer ones. After the gel has run for awhile, the shortest pieces of DNA will be close to the positive end of the gel, while the longest pieces of DNA will remain near the wells. Very short pieces of DNA may have run right off the end of the gel if we left it on for too long.

Visualizing the DNA Fragments

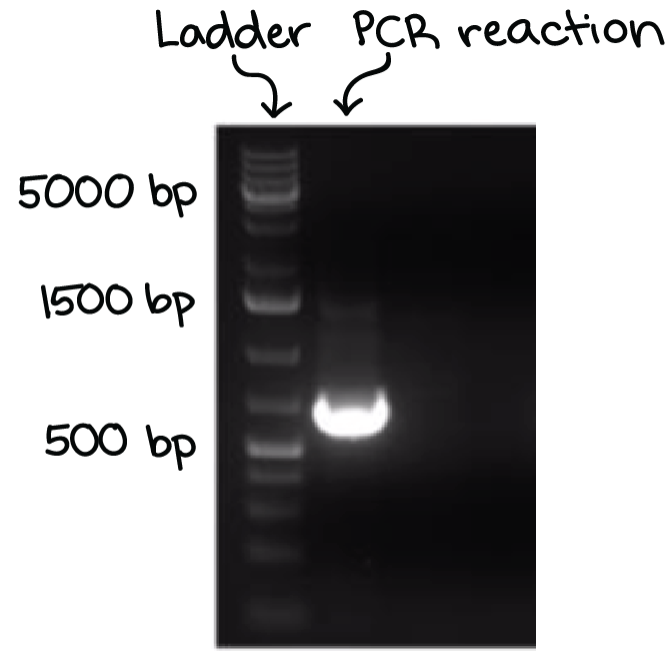

Once the fragments have be separated, we can examine the gel and see what sizes of bands are found on it. When a gel is stained with a DNA-binding dye and placed under UV lights, the DNA fragments will glow, allowing us to see the DNA present at different locations along the length of the gel.

A well-defined “line” of DNA on ta gel is called a band. Each band contains a large number of DNA fragments of the same size that have traveled as a group to the same position. A single DNA fragment (or even a small group of DNA fragments) would not be visible by itself on a gel.

By comparing the bands in a sample to the DNA ladder, we can determine their approximate sizes. For instance, the bright band on the gel above is roughly 700 base pairs (bp) in size.

Team 2: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Scientists need significant amounts of DNA to study it. Sometimes, only a small piece of DNA is available. Scientists must amplify, or copy, these small pieces to create large amounts of DNA. They do this by using a technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It is a fast and inexpensive way to amplify small pieces of DNA.

What is PCR used for? The DNA produced by PCR can be used in many different laboratory procedures. PCR is used in DNA fingerprinting, or the process of determining a person’s characteristics through their DNA. Itis also helpful in the diagnosis of disorders related to genes and in the detection of bacteria or viruses.

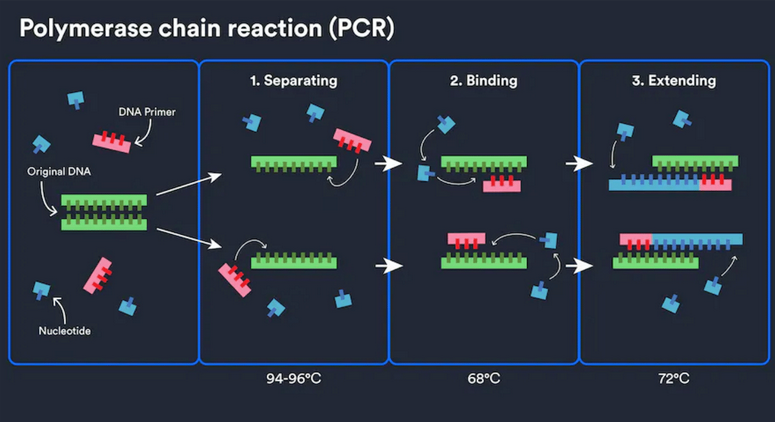

How does it work? The PCR process can be done by a machine in just a few hours. The machine is called a thermocycler. It alters the temperature of the reaction every few minutes. The steps are as follows:

- The machine heats the DNA sample to a high temperature, denaturing the DNA into 2 pieces of single-stranded DNA.

- The machine lowers the temperature, allowing a short stretch of DNA, known as a primer, to bind to the single strands. The primer acts as a signal for the enzyme Taq polymerase.

- The machine raises the temperature again, allowing the Taq polymerase enzyme to synthesize two new strands of DNA using the original strands as templates. This process results in a copy of the original DNA. Each of the new molecules contains 1 old and 1 new strand of DNA. These strands can be used to create two new copies, and so on, and so on.

The cycle of denaturing and synthesizing new DNA is repeated as many as 30 or 40 times. This leads to more than 1 billion exact copies of the original DNA segment.

Team 3: Gene Cloning

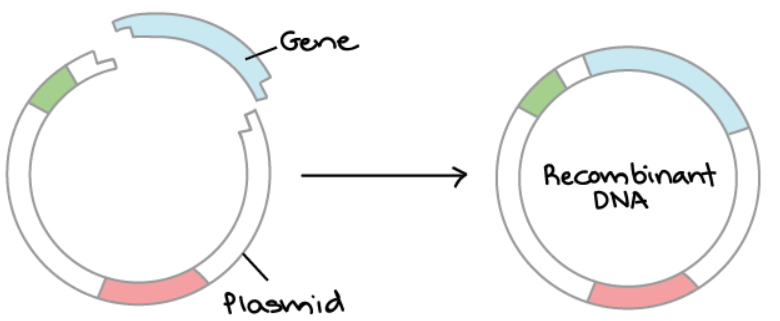

Overview of DNA Cloning DNA cloning is the process of making multiple, identical copies of a particular piece of DNA. In a typical DNA cloning procedure, the gene or other DNA fragment of interest (perhaps a gene for a medically important human protein) is first inserted into a circular piece of DNA called a plasmid. The insertion is done using enzymes that “cut and paste” DNA, and it produces a molecule of recombinant DNA, or DNA assembled out of fragments from multiple sources.

Next, the recombinant plasmid is introduced into bacteria. Bacteria carrying the plasmid are selected and grown up. As they reproduce, they replicate the plasmid and pass it on to their offspring, making copies of the DNA it contains.

What is the point of making many copies of a DNA sequence in a plasmid? In some cases, we need lots of DNA copies to conduct experiments or build new plasmids. In other cases, the piece of DNA encodes a useful protein, and the bacteria are used as “factories” to make the protein. For instance, the human insulin gene is expressed in E. coli bacteria to make insulin by diabetics.

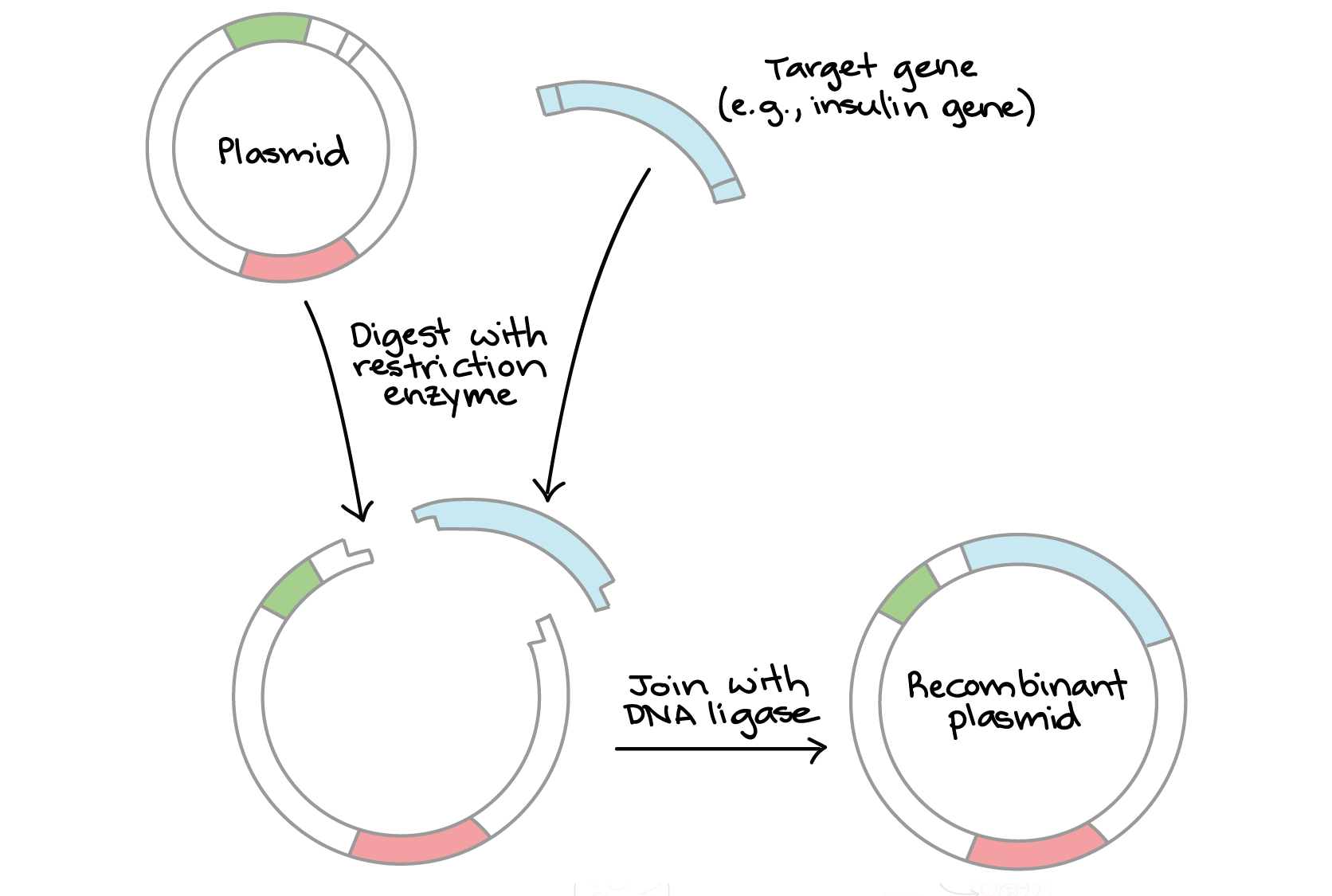

Steps of DNA Cloning One example of DNA cloning is used to synthesize a protein in bacteria. The basic steps are:

- Cut open the plasmid and “paste” in the gene. This process relies on restriction enzymes (which cut DNA) and DNA ligase (which joins DNA).

- Insert the plasmid into bacteria. Use antibiotic selection to identify the bacteria that took up the plasmid.

- Grow up lots of plasmid-carrying bacteria and use them as “factories” to make the protein. Harvest the protein from the bacteria and purify it.

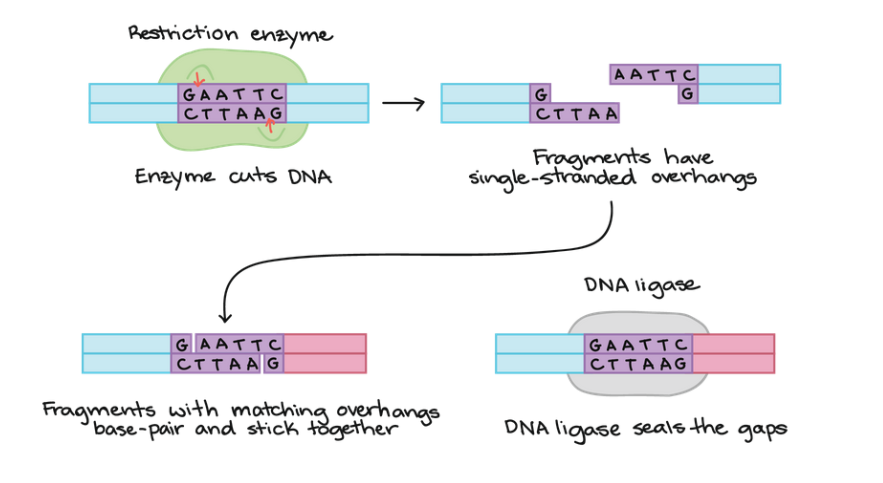

1. Cutting and Pasting DNA To join together pieces of DNA from different sources, scientists commonly use two types of enzymes: restriction enzymes and DNA ligase.

A restriction enzyme is a DNA-cutting enzyme thar recognizes a specific target sequence and cuts DNA into two pieces at or near that site. Many restriction enzymes produce cut ends with short, sing-stranded overhangs. If two molecules have matching overhangs, they can base-pair and stick together. However, they won’t combine to form an unbroken DNA molecule until they are joined by DNA ligase, which seals gaps in the DNA backbone.

In cloning, the goal is to insert a target gene (e.g., for human insulin) into a plasmid. Using a carefully chosen restrictive enzyme, we digest:

- The plasmid, which has a single cut site

- The target gene fragment, which has a cut site near each end.

Then, we combine the fragments with DNA ligase, which links them to make a recombinant plasmid containing the gene.

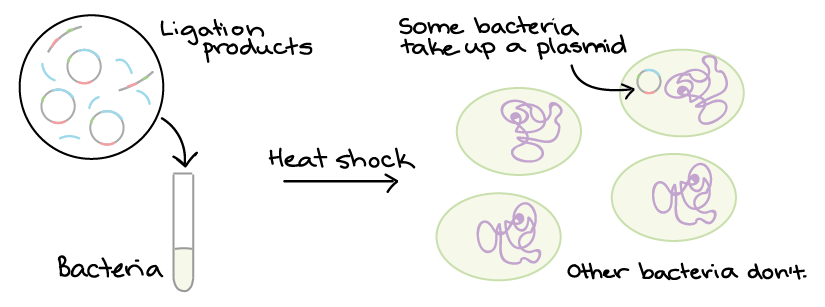

2. Bacterial Transformation and Selection Plasmids and other DNA can be introduced into bacteria, such as the harmless E. coli used in labs, in a process called transformation. During transformation, specifically prepared bacterial cells are given a shock (such as high temperature) that encourages them to take up foreign DNA.

Not all colonies will necessarily contain the right plasmid. That’s because during ligation, DNA fragments don’t always get “pasted” in exactly the way we intend. Instead, we must contain DNA from several colonies and see whether each one contain the right plasmid. Methods like restriction enzyme digestion and PCR are commonly used to check the plasmids.

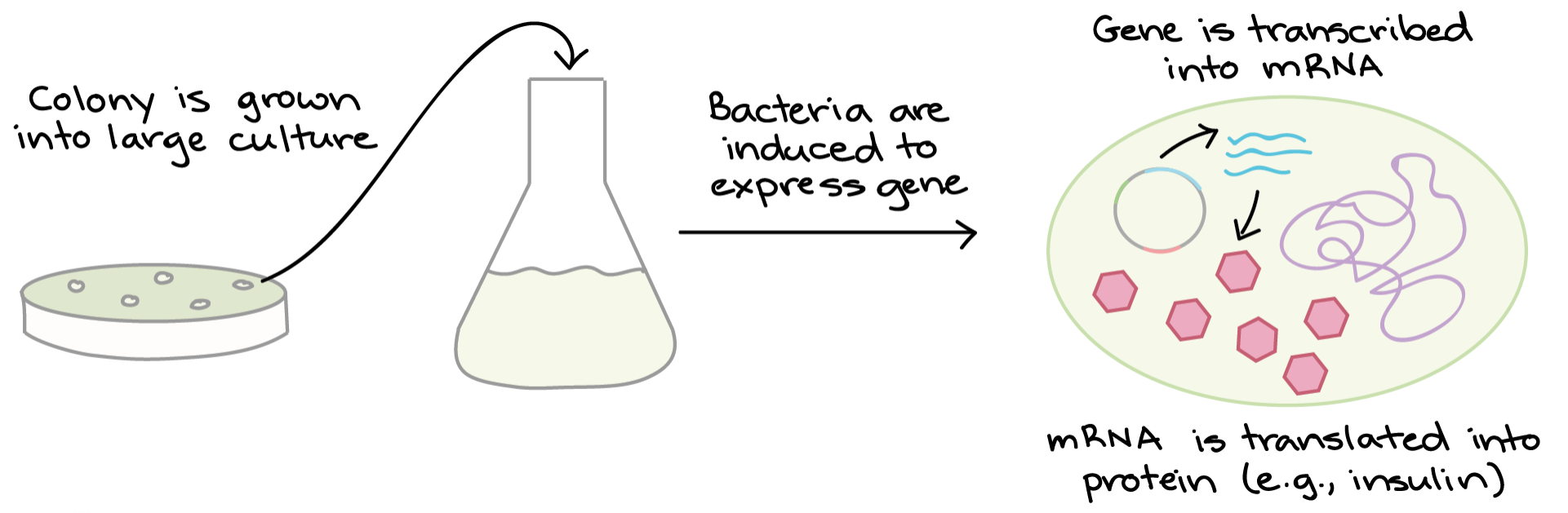

3. Protein Production Once we have found a bacterial with the right plasmid, we can grow a large culture of plasmid-bearing bacteria. Then, we give the bacteria a chemical signal that instructs them to make a target protein.

The bacteria serves as miniature “factories,” churning out large amounts of proteins. For instance, if our plasmid contained the human insulin gene, the bacteria would start transcribing the gene and translating the mRNA to produce man molecules of human insulin protein.

Once the protein has been produced, the bacterial cells can be split open to release it. There are many other proteins and macromolecules floating around in bacteria besides the target protein (e.g., insulin). Because of this, the garget protein must be purified, or separated from the other contents of the cells by biochemical techniques. The purified protein can be used for experiment or, in the case of insulin, administered to patients.

Uses of DNA Cloning DNA molecules built through cloning techniques are used for many purposes in molecular biology. A short list of examples includes:

- Biopharmaceuticals. DNA cloning can be used to make human proteins with biomedical applications, such as the insulin mentioned above. Other examples of recombinant proteins include human growth hormone, which is given to patients who are unable to synthesize the hormone, and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which is used to treat strokes and prevent blood clots. Recombinant proteins like these are often made in bacteria.

- Gene therapy. In some genetic disorders, patients lack the functional form of a particular gene. Gene therapy attempts to provide a normal copy of the gene to the cells of a patient’s body. For example, DNA cloning was used to build plasmids containing a normal version of the gene that’s nonfunctional in cystic fibrosis. When the plasmids were delivered to the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, lung function deteriorated less quickly

- Gene analysis. In basic research labs, biologists often use DNA cloning to build artificial, recombinant versions of genes that help them understand how normal genes in an organism function.

These are just a few examples of how DNA cloning is used in biology today. DNA cloning is a very common technique that is used in a huge variety of molecular biology applications.

Team 4: CRISPR CRISPR-Cas9, or more commonly just CRISPR, is a simple, cheap, and effective gene-editing system. CRISPR can potentially kill of malaria-carrying mosquitos, make wheat invulnerable to blight, produce eggs available to people allergic to them, and bring a woolly mammoth back from extinction.

Researchers have used CRISPR to repair a mutation that causes blindness, remove HIV from immune cells, and correct the defect responsible for cystic fibrosis.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a rudimentary immune system that Japanese scientists first noticed in bacteria nearly 30 years ago. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats are sequences of genetic code broken up by remnants of genes from past invaders that help bacteria identify them when they appear again so the Cas9 enzyme can slice through them.

The gene-editing system isn’t perfect, at least not yet. It makes unintended cuts in DNA as often as 60 percent of the time in some applications, with effects unknown.