Introduction

Proteins are among the most abundant organic molecules in living systems and are way more diverse in structure and function than other classes of macromolecules. A single cell can contain thousands of proteins, each with a unique function. Although their structures, like their functions, vary greatly, all proteins are made up of one or more chains of amino acids.

Types and Functions of Proteins

Proteins can play a wide array of roles in a cell or organism.

Enzymes

Enzyme act as catalysts in biochemical reactions, meaning that they speed the reactions up. Each enzyme recognizes one or more substrates, the molecules that serve as starting material for the reaction it catalyzes. Different enzymes participate in different types of reactions and may break down, link up, or rearrange their substrates.

One example of an enzyme found in your body is salivary amylase, which breaks amylose (a kind of starch) down into smaller sugars. The amylose doesn’t taste very sweet, but the smaller sugars do. This is why starchy foods often taste sweeter if you chew them for longer: you’re giving salivary amylase time to get to work.

Hormones

Hormones are long-distance chemical signals released by endocrine cells (like the cells of your pituitary gland). They control specific physiological processes, such as growth, development, metabolism, and reproduction. While some hormones are steroid-based, others are proteins. These protein-based hormones are commonly called peptide hormones.

For example, insulin is an important peptide hormone that helps regulate blood glucose levels. When blood glucose rises (for instance, after you eat a meal), specialized cells in the pancreas release insulin. The insulin binds to cells in the liver and other parts of the body, causing them to take up the glucose. This process helps return blood sugar to its normal, resting level.

Protein Types and Functions

| Role | Examples | Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Digestive enzyme | Amylase, lipase, pepsin | Break down nutrients in food into small pieces that can be readily absorbed |

| Transport | Hemoglobin | Carry substances throughout the body in blood or lymph |

| Structure | Actin, tubulin, keratin | Build different structures, like the cytoskeleton |

| Hormone signaling | Insulin, glucagon | Coordinate the activity of different body systems |

| Defense | Antibodies | Protect the body from foreign pathogens |

| Contraction | Myosin | Carry out muscle contraction |

| Storage | Legume storage proteins, egg white (albumin) | Provide food for the early development of the embryo or the seedling |

| A protein’s shape is critical to its function, and many different types of chemical bonds may be important in maintaining this shape. Changes in temperature and [[pH | pH]], as well as the presence of certain chemicals, may disrupt a protein’s shape and cause it to lose functionality, a process known as [[Denaturation | denaturation]]. |

Amino Acids

Amino acids are the monomers that make up proteins. Specifically, a protein is made up of one or more linear chains of amino acids, each of which is called a polypeptide. There are 20 types of amino acids commonly found in proteins.

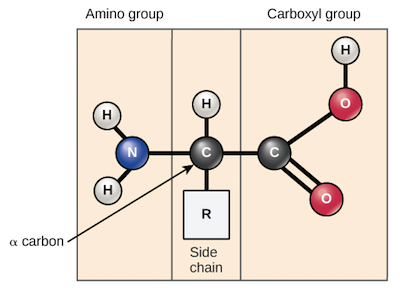

Amino acids share a basic structure, which consists of a central carbon atom, also known as the alpha (α) carbon, bonded to an amino group (), a carboxyl group (), and a hydrogen atom.

Although the generalized amino acid shown above is shown with its amino and carboxyl groups neutral for simplicity, this is not actually the state in which an amino acid would typically be found. At physiological pH (7.2 - 7.4), the amino group is typically protonated and bears a positive charge, while the carboxyl group is typically deprotonated and bears a negative charge.

Every amino acid also has another atom or group of atoms bonded to the central atom, known as the R group, which determines the identity of the amino acid. For instance, if the R group is a hydrogen atom, then the amino acid is glycine, while if it’s a methyl () group, the amino acid is alanine. The twenty common amino acids are shown in the chart below, with their R groups highlighted in blue.

A few other amino acids have R groups with special properties:

- Proline has an R group that’s linked back to its own amino group, forming a ring structure. This makes it an exception to the typical structure of an amino acid, since it no longer has the standard amino group. The odd ring structure is because proline often causes bends or kinks in amino acid chains.

- Cysteine contains a thiol (-SH) group and can form covalent bonds with other cysteines.

Finally, there are a few other “non-canonical” amino acids that are found in proteins only under certain conditions.

Peptide Bonds

Each protein in your cells consists of one or more polypeptide chains. Each of these polypeptide chains is made up of amino acids, linked together in a specific order. A polypeptide is kind of like a long word that is “spelled out” in amino acid letters. The chemical properties and order of the amino acids are key in determining the structure and function of the polypeptide, and the protein it’s part of.

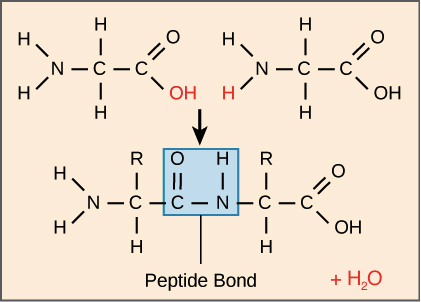

The amino acids of a polypeptide are attached to their neighbors by covalent bonds known as a peptide bonds. Each bond forms in a dehydration synthesis reaction. During protein synthesis, the carboxyl group of the amino acid at the end of the growing polypeptide chain chain reacts with the amino group of an incoming amino acid, releasing a molecule of water. The resulting bond between amino acids is a peptide bond.

Because of the structure of the amino acids, a polypeptide chain has directionality, meaning that it has two ends that are chemically distinct from one another. At one end, the polypeptide has a free amino group, and this end is called the amino terminus (or N-terminus). The other end, which has a free carboxyl group, is known as the carboxyl terminus (or C-terminus). The N-terminus is on the left and the C-terminus is on the right for the very short polypeptide shown above.