Homeostasis is the state of steady internal physical and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and includes many variables, such as body temperature and fluid balance, being kept within certain pre-set limits (homeostatic range). Other variables include the pH of extracellular fluid, the concentrations of sodium, potassium, and calcium ions, as well as the blood sugar level, and these need to be regulated despite changes in the environment, diet, or level of activity. Each of these variables is controlled by one or more regulators or homeostatic mechanisms, which together maintain life.

Maintaining Homeostasis

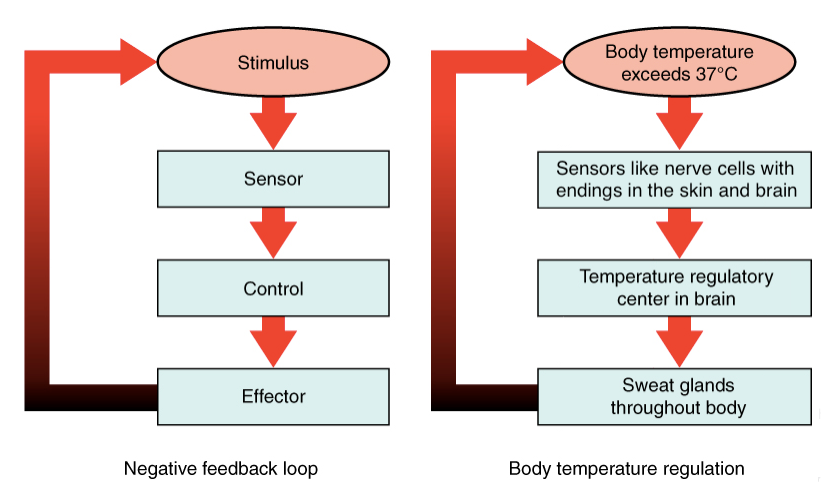

Maintenance of homeostasis usually involves negative feedback loops. These loops act to oppose the stimulus, or cue, that triggers them. For example, if your body temperature is too high, a negative feedback loop will act to bring it back down towards the set point, or target value, of /.

irst, high temperature will be detected by sensors—primarily nerve cells with endings in your skin and brain—and relayed to a temperature-regulatory control center in your brain. The control center will process the information and activate effectors—such as the sweat glands—whose job is to oppose the stimulus by bringing body temperature down.

In general, homeostatic circuits usually involve at least two negative feedback loops:

- One is activated when a parameter—like body temperature—is above the set point and is designed to bring it back down.

- One is activated when the parameter is below the set point and is designed to bring it back up.

Disruptions to feedback disrupt homeostasis

Homeostasis depends on negative feedback loops. So, anything that interferes with the feedback mechanisms can—and usually will—disrupt homeostasis. In the case of the human body, this may lead to disease.

Diabetes, for example, is a disease caused by a broken feedback loop involving the hormone insulin. The broken feedback loop makes it difficult or impossible for the body to bring high blood sugar down to a healthy level.

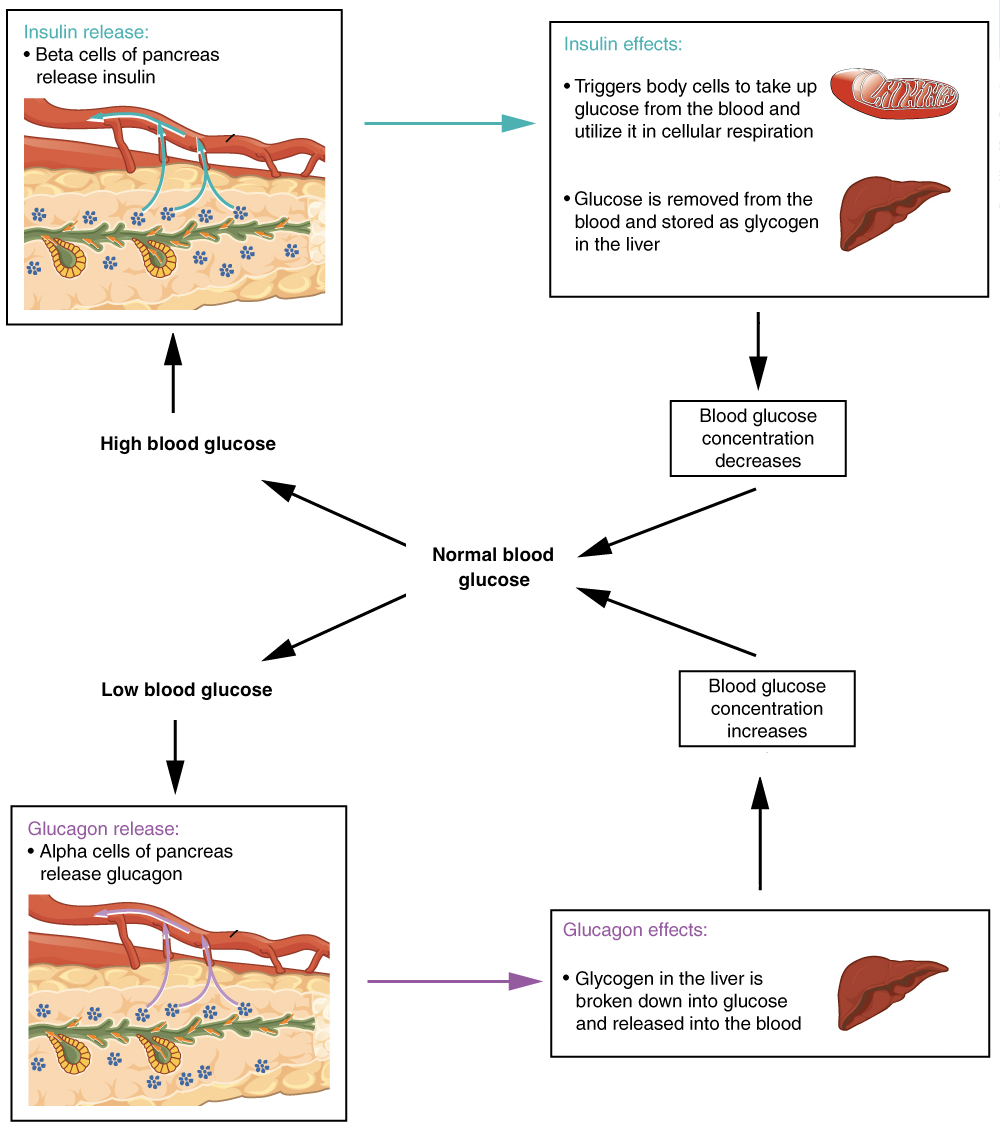

To appreciate how diabetes occurs, let’s take a quick look at the basics of blood sugar regulation. In a healthy person, blood sugar levels are controlled by two hormones: insulin and glucagon.

Insulin decreases the concentration of glucose in the blood. After you eat a meal, your blood glucose levels rise, triggering the secretion of insulin from β cells in the pancreas. Insulin acts as a signal that triggers cells of the body, such as fat and muscle cells, to take up glucose for use as fuel. Insulin also causes glucose to be converted into glycogen—a storage molecule—in the liver. Both processes pull sugar out of the blood, bringing blood sugar levels down, reducing insulin secretion, and returning the whole system to homeostasis.

Glucagon does the opposite: it increases the concentration of glucose in the blood. If you haven’t eaten for a while, your blood glucose levels fall, triggering the release of glucagon from another group of pancreatic cells, the α cells. Glucagon acts on the liver, causing glycogen to be broken down into glucose and released into the bloodstream, causing blood sugar levels to go back up. This reduces glucagon secretion and brings the system back to homeostasis.

Diabetes happens when a person’s pancreas can’t make enough insulin, or when cells in the body stop responding to insulin, or both. Under these conditions, body cells don’t take up glucose readily, so blood sugar levels remain high for a long period of time after a meal. This is for two reasons:

- Muscle and fat cells don’t get enough glucose, or fuel. This can make people feel tired and even cause muscle and fat tissues to waste away.

- High blood sugar causes symptoms like increased urination, thirst, and even dehydration. Over time, it can lead to more serious complications.

Positive Feedback Loops

Homeostatic circuits usually involve negative feedback loops. The hallmark of a negative feedback loop is that it counteracts a change, bringing the value of a parameter—such as temperature or blood sugar—back towards it set point.

Some biological systems, however, use positive feedback loops. Unlike negative feedback loops, positive feedback loops amplify the starting signal. Positive feedback loops are usually found in processes that need to be pushed to completion, not when the status quo needs to be maintained.

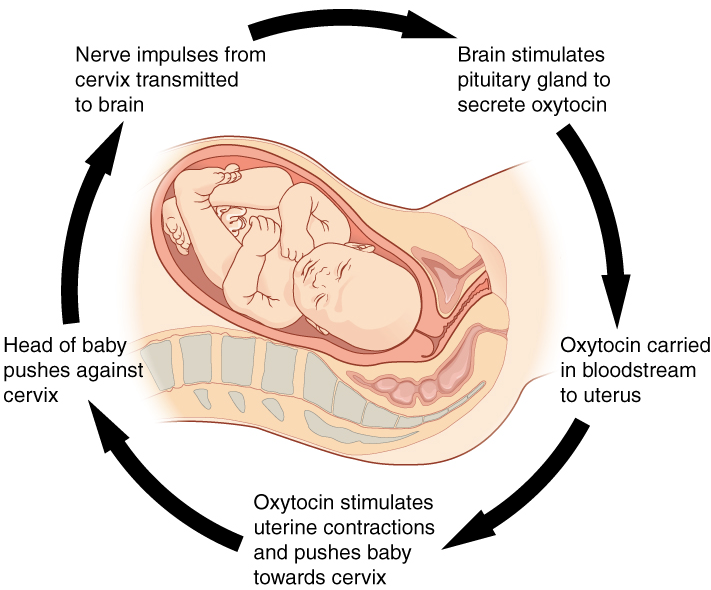

A positive feedback loop comes into play during childbirth. In childbirth, the baby’s head presses on the cervix—the bottom of the uterus, through which the baby must emerge—and activates neurons to the brain. The neurons send a signal that leads to release of the hormone oxytocin from the pituitary gland.

Oxytocin increases uterine contractions, and thus pressure on the cervix. This causes the release of even more oxytocin and produces even stronger contractions. This positive feedback loop continues until the baby is born.